Hyphenation and the role of archival practice and memory in the production of identity and the self.

Introduction

Mnemosyne (45 mins), named after the Greek goddess of memory, is an installation version of John Akomfrah’s film The Nine Muses (90 mins). Mnemosyne uses archival material from the BCC and ITV to “recast and retell” (Mnemosyne, 2010) the experience of post-war immigrants in Britain. Centred on the West Midlands from 1960 - 1981, it’s mixed with footage of lone figures, frozen landscapes, and vast seas (figs. 1 & 2), against a soundtrack made up of various stories, songs, and poems. There is no one narrator or narrative that underpins the work; the chapters/verses are named after the nine muses. Homer's Odyssey introduces the theme of a journey, Milton’s Paradise Lost draws on the question of belonging, and Beckett’s Molloy introduces the idea of the mother; of origin.

Figure 1. & 2. Stills from Mnemosyne (Akomfrah, 2010)

Mnemosyne maps the lives of post-war immigrants through these cartographical concepts of journeys, belonging, and origins. It was created out of the paradox of immigrant identities existing in a space where there are very few indications, memorials or epitaphs that reference the fact that they exist in the location they immigrated to. At the same time, there is quite a lot of information about what they now mean to this new location and for the dominant culture (Map Marathon, 2010: Mnemosyne, 2016). Mnemosyne provides a counter-cartography by looking at how archival material illustrates dominant narratives, interrogating the absences, gaps and lacks, and forcing the material to say something else; something about the desires of these individuals, something that grants these individuals legitimacy (Map Marathon, 2010: Mnemosyne, 2016).

As a hyphenated (mixed-race) individual whose father immigrated to Britain in the 1970s, Mnemosyne spoke to the questions I have always had around belonging. It broadened my understanding of colonial history through a new lens and showed me that reading between the lines can be a form of resistance. Through Akomfrah’s writing, I found the language I was missing when it came to articulating my experiences. When reading between the lines or producing new readings, we inevitably find absences, gaps, and lack; narratives unaccounted for, individuals or whole groups who have been erased, and systems that fail to account for that which lies outside of their neat prescriptions.

This essay explores how systems of classification produce ‘the hyphen’ and what that means for the hyphenated individual (Chapter 1). It then moves on to explore how the reinforcement of dominant narratives and systems of classification lead to resistance. I use institutional archives as an example of where this reinforcement can be seen. This resistance takes the form of reconstructions and alternative readings in service of producing new narratives which speak to the experience of hyphenated individuals. Memory is a mode through which the hyphenated individual can produce new narratives that speak to their individual experiences (Chapter 2). Through reading between the lines and engaging with new narratives, the hyphenated individual can redefine themselves. These processes of resistance, redefinition, and reconstruction aid and mirror the development of the hyphenated individual's identity and concept of self (Chapter 3).

Chapter 1 - Classification and Hyphenation

“Like a cool breeze, he turned his shapelessness into a form of resistance.” – Will Harris

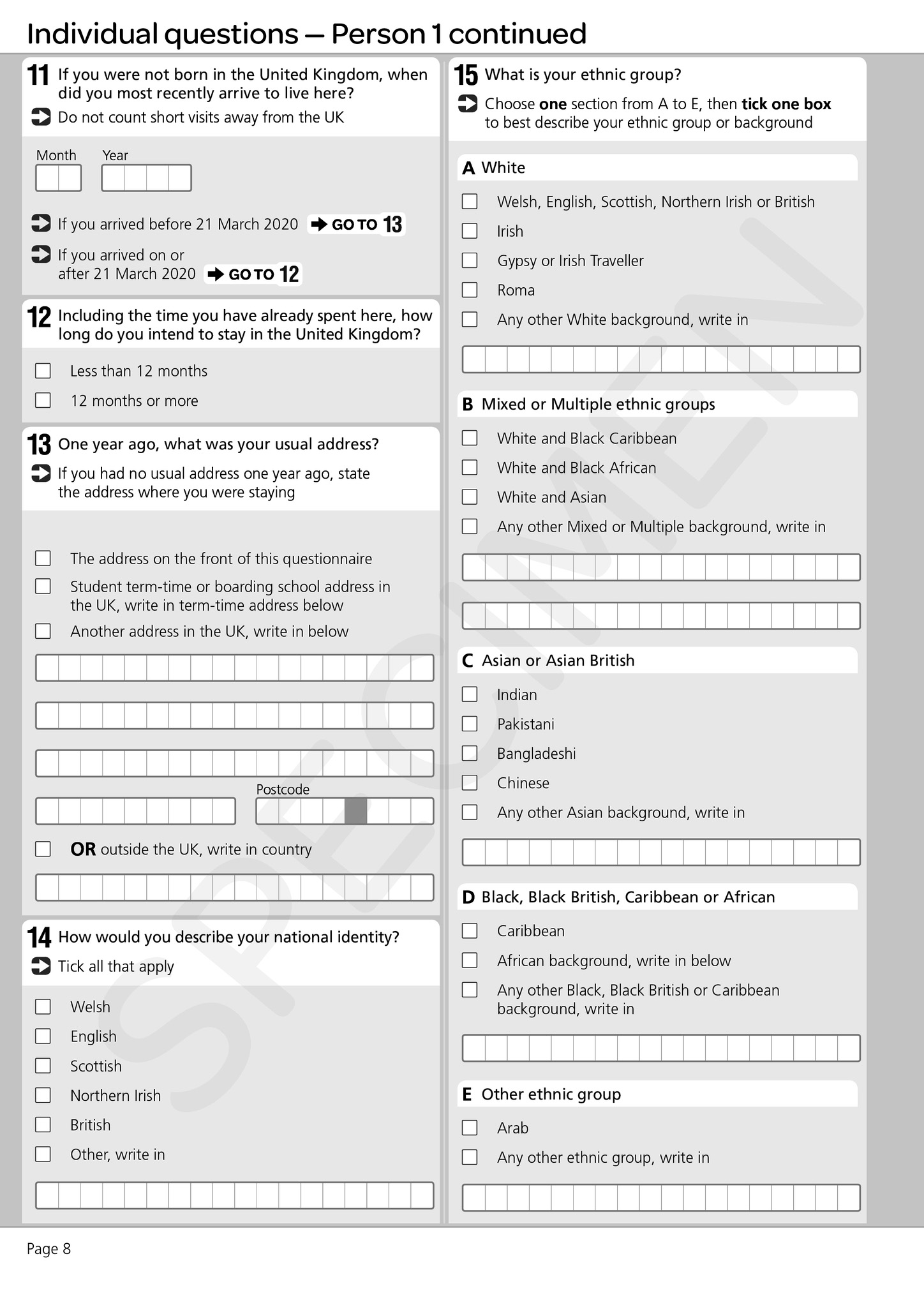

Figure 3. The ethnic group question from the 2021 Census (Census 2021 – England & Wales, 2019)

Assimilation is a benevolent response to the problem of othering, and the Census (fig.3), provides the language for this assimilation by demanding that marginalised groups must adopt an identity which is dictated by the dominant group or exist as only 'other' (Menendian and Powell, n.d). The Census is an example of othering that is a product of state-level bureaucracy. It trickles down into our lives, asking us to submerge or repress parts of our identity that do not fit neatly into the boxes provided.

Systems of classification are used to generate or organise meaning; a fundamental aspect of human culture. However, when these systems become “objects of the disposition of power” (Hall, 1997, p.2), issues arise as they provide a framework through which institutions of power justify the differential treatment of minority groups. Imbuing these classifications with a context that shifts their function from the descriptive to prescriptive, shaping individual experiences under a racial schema. Systems of classification lend themselves to “centering the perspectives and experiences of privileged groups, creating, and maintaining social hierarchies” (Krook, 2020, p.188), through strategies of exclusion and differentiation. The Census is an example of one of these systems; it asks us to pick a singular description for our ethnic identity from a list that uses the word ‘other’ for those who do not fit into the neat categories that have been outlined.

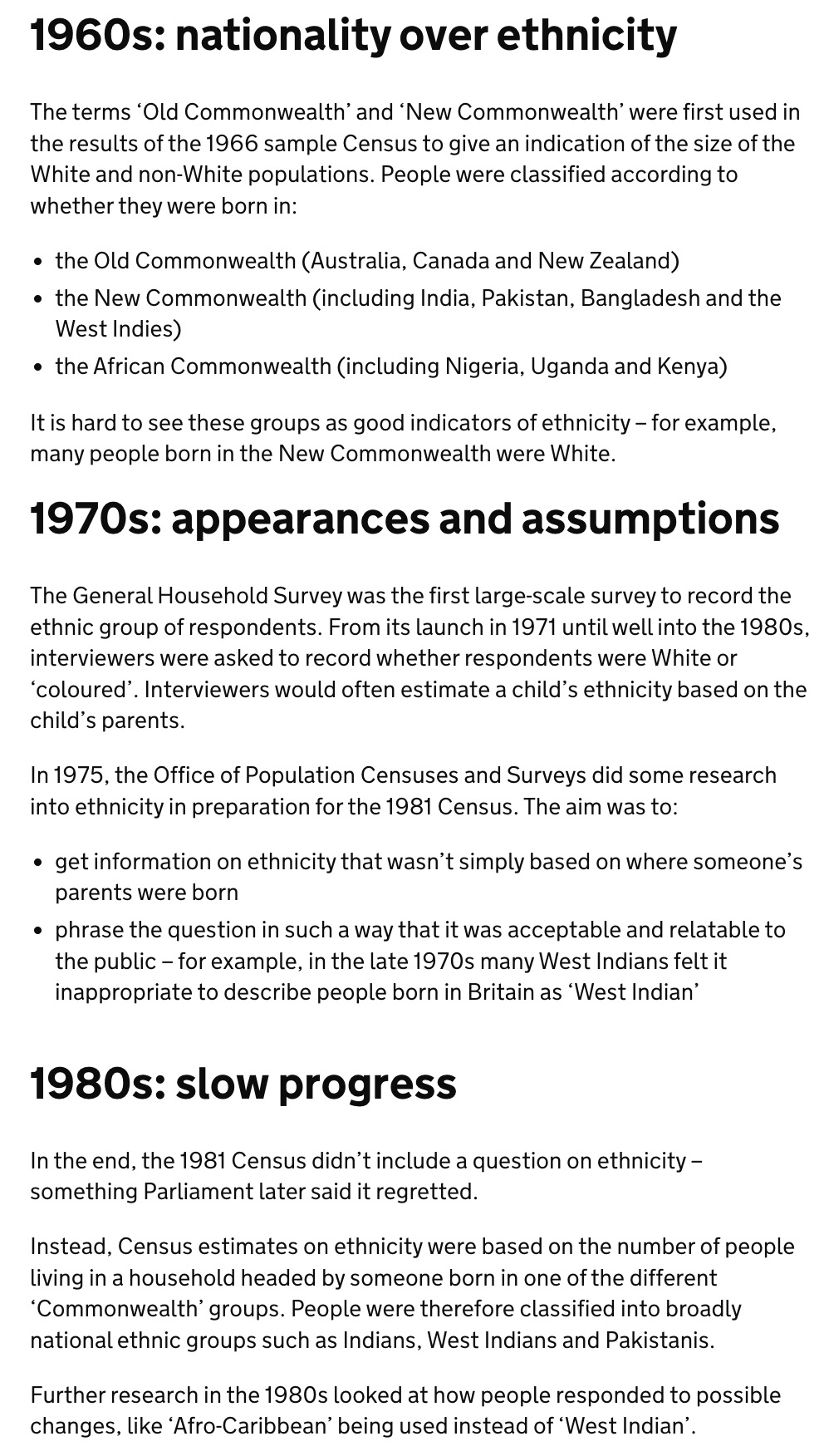

A product of the inability of certain individuals to fit into these binary categories is a form of ‘hyphenation’. This hyphenation produces the hyphenated individual: this individual does not fit into the dominant systems of classification, so new categories were created, such as Black-British, Mixed-Race, and so on (Akomfrah, Scotini and Galasso, 2016, p.23-36). For the hyphenated individual in the 20th century, these strategies of differentiation were made abundantly clear through immigration and the movement of individuals from colonies to Britain, a by-product of the Empire. The opening lines of John Akomfrah’s Mnemosyne illustrate and interrogate the sentiment: “Sometimes we think we shouldn't blame the people because it is we who came to their country. On the other hand, we think that, if they in the first place had not come to our country and spread a false propaganda, we would never have come to theirs” (Mnemosyne, 2010). This feeling would not have been shared by all, and it is certainly not the sentiment echoed in dominant narratives that surround immigration. Individuals arrived, and their cultural or ethnic identity could not be accounted for by existing categories, so new systems were formed, producing the hyphen. (fig. 4). Akomfrah likens the creation or production of the hyphen to “going to the moon – people were literally altered, psychically, psychologically, physically, by a process of their journey. They left one space and were never the same again” (Budzinski, 2012).

Figure 4. 50 years of collecting ethnicity data (Laux, 2019)

“In every Census since 1841, people have been asked to state their country of birth and, in most cases, their nationality. However, asking about people’s ethnicity is a relatively new concept” (Laux, 2019).

For the hyphenated individual in the 21st century, the discomfort caused by these categories is wrapped up in British post-imperial assimilation and integration; one that requires the individual to fit themselves into a box. Even when these boxes or categories have been expanded, the hyphenated individual is either in excess of this box or fits uncomfortably within it. When holding multiple cultural or racial identities, a singular descriptor is not enough because their existence is encapsulated by the reality that “one is too few and two is too many — no single idea can make sense on its own, but no two ideas can be grasped simultaneously” (Harris, 2018, p.8). The hyphenated individual is trapped between being too much of one and not enough of the other when it comes to their heritage and the cultures they embody.

The hyphen is a blurred line. Akomfrah wrote about “the moment of the hyphen: the moment a group comes to self-realisation; when it senses that its concept of self is emerging as a result of strategies of exclusion and differentiation that it had initially understood as normative injunctions” (Akomfrah, Scotini and Galasso, 2016, p.26). This self-realisation solidifies the shapelessness, the blurriness, of the hyphenated individual. The hyphen speaks to the absences, gaps and lacks felt when we cannot level our lived experiences with the dominant narrative, with the way the 'world works'. This is a feeling not limited to the hyphenated individual, but it is more easily articulated or more apparent when we explore their experiences. They begin to understand that “there are elements [they] comprise that are not wholly or completely 'narrated' by the prevailing legitimatising narratives” (Akomfrah, Scotini and Galasso, 2016, p.26), and a process of redefinition can begin. For the hyphenated individual, this process of defining oneself is more than an active process in which the individual can undergo their own process of meaning construction and come to understand themselves. It is concerned with a redefinition that is divorced from the framework of classifications, dominant narratives or ‘othering’, a redefinition of their own understanding through their own construction.

Chapter 2 - Reinforcement and Resistance

“If it were not for the visions afforded by memories of one’s own life, one would not be able to understand the lives of others.” — Mary Warnock

Systems of classification and dominant narratives are echoed and reinforced within institutional archives. Institutional archives follow very strict guidelines. They are organised and controlled, their contents being disconnected from their time of creation but used as signifiers of the past, of history. “Archives form one of the interfaces with the past, along with other formal structures like museums, libraries, and monuments” (Hedstrom, 2002, p.27). Histories and experiences can never be fully encompassed, even by a structure that aims to acquire, store, and make available these histories (Millar, 2006) as a result of the inherent constraints within archival practices and their structures. Additionally, acquisition and storage cannot be divorced from systems of inclusion and exclusion, which take the institutional archive from a place of “mere storage” into being a “place of dispute” (Barbosa and Voto, 2021). These systems are influenced by historical perspectives, power and control, and the archival process influences how marginalised people are represented. The content within the institutional archive is not comprehensive but rather constructed, reflecting these systems and processes. “Only those voices that conform to the ideals of those in power are allowed into the archive; those that do not conform are silenced” (Carter, 2006, p.219). These silenced voices leave absences, gaps and lacks in institutional archives when the “marginalised are denied access and entry into the archive as a result of their peripheral position in society” (Carter, 2006, p.219).

The strict guidelines and structures of the institutional archive creates the opportunity for resistance because when individuals begin to recognise that they are not represented by the dominant narratives it reinforces, they begin to ask the question: where am I represented? “The naming of the silence subverts it, draws attention to it. The lack, the unsaid, determines and defines the very existence of what is said” (Carter, 2006, p.222). Institutional archives, by their nature, are unable to reflect experiences that do not fit into the narratives they represent. The implications of this on our lives, and specifically the lives of hyphenated individuals, is that these narratives, which they do not exist within, are then reflected in the institutional social memory (which excludes them). Institutional social memory describes the collective knowledge, narratives, and representations preserved and perpetuated within formal organizations, institutions, or societal structures (Olick and Robbins, 1998). An example of the influence of institutional social memory can be seen in media coverage of immigration and migration, which is filled with language that alludes to water. Immigrants 'flood' our societies, 'streaming' and 'pouring' across borders onto our shores. Imagery of boats, life jackets and ocean-based transit occupy our news sources. This language has been used to construct a narrative about how immigrants arrive at a new place and the unstoppable force with which they arrive. The power of this narrative erases the stories of immigrants and migrants who have not travelled by sea, who do not exist within this myth, and dehumanises those who do by likening their arrival to an unstoppable wave that threatens borders and bureaucracy (Kainz, 2016).

In Mnemosyne, Akomfrah shows us a method of resistance. He asks the question: “How do you unburden images of the past with certain associations?” Because people look at archives of our recent past, especially ones that involve migration, and they think they know what it says because, on the whole, television has told them what those images mean (Budzinski, 2012). He finds the fragments where the marginalised are represented, on the edges of archival footage, in the corners, sides, and at the fringes. In the institutional archives he uses (BBC and ITV archives), immigrants are “filmed coming off the boat, they just fall off into obscurity and you never see them again” (Budzinski, 2012).

Akomfrah finds the moments when we do see them again in spite of their removal or exclusion from the dominant narratives represented in institutional archives. It is through this process of “reading between the lines” and looking to the fragments that Akomfrah illuminates the absences, gaps and lacks within institutional archives; when stories are left untold, entire sets of experiences are left out, and the existence of various groups are denied or ignored. By reconstructing the material through an alternative reading, he shows us that while the archive seems to say “these people never existed” or “their experiences are not as significant as ours in the story of this country”, we see that, in fact, they did exist, and they are as significant. He is not interested in “propping up some fiction and myth of Britishness and how the hyphen or Black Britain was created” (Budzinski, 2012). By extension, he is not interested in using the institutional archive as it comes to us. His construction of a counter-cartography is a form of resistance. Institutional archives often streamline diverse experiences into homogenised narratives that fail to capture the nuanced, multifaceted nature of individual identities and experiences. Akomfrah demonstrates how a new reading of the material can legitimise experiences that exist in between, or outside, the dominant narrative threads. Through this new reading of archival material, he shows us that the narratives in institutional social memory are not actually an accurate reflection of what exists in these institutional archives but are also a construction produced from a particular reading.

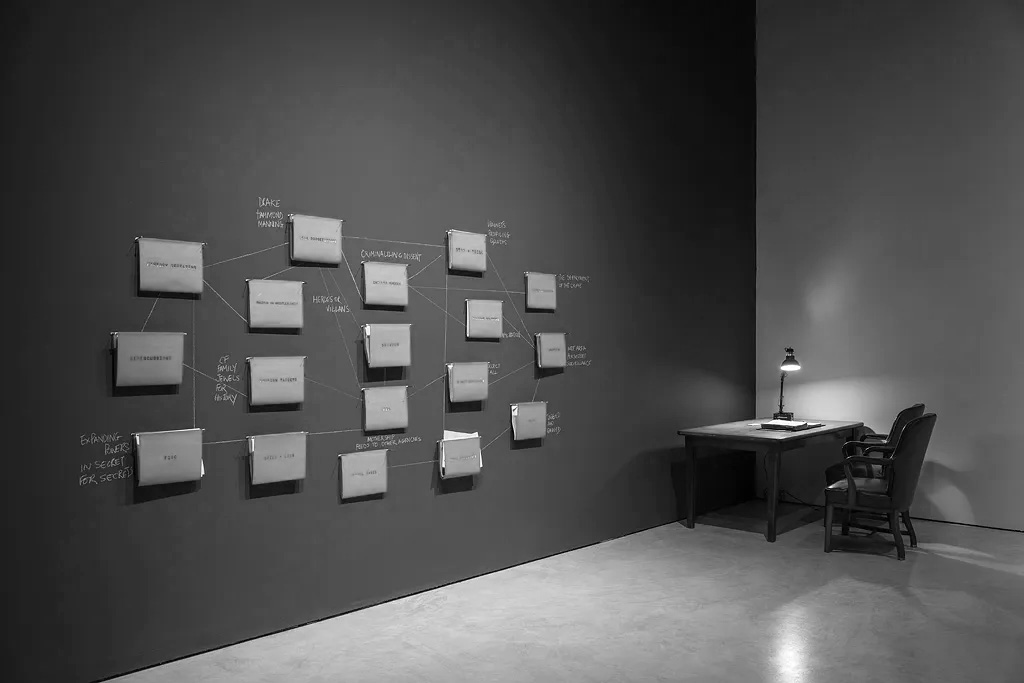

In her work Index of the Disappeared (figs 6 & 7), Mariam Ghani gives us another method of resisting the dominant narratives which influence institutional social memory. Where Akomfrah uses institutional archives in his resistance, Ghani produces a counter-narrative by creating her own archive that draws attention to and fills in some of the absences, lacks and gaps found in institutional archives. Index of the Disappeared’ “foregrounds the difficult histories of immigrant, ‘Other’ and dissenting communities in the U.S. since 9/11, as well as the effects of U.S. military and intelligence interventions around the world” (Ghani, 2004). By ‘bringing the hidden, the marginalised, the exile, the ‘other’ archive, into the mainstream, [she] allows that archive to trouble conceptualisations of the mainstream’ (Carter, 2006, p.226). Through ‘presenting the Index archive as an artwork-in-progress, constantly re-adapted to the specific sites in which it is installed, [she] encourages visitors to approach it not as researchers seeking facts but rather with the critical awareness that the ‘facts’ they encounter are in flux, defined and redefined in relationship to time, to their context and to each other’ (Ghani, 2004). Through these processes of presentation, adaptation, and installation, Ghani resists dominant narratives that influence institutional social memory by encouraging people to engage with a new perspective, a new narrative. This is something the institutional archive does not do – it often presents itself as a container of ultimate histories rather than a space that shifts and flows depending on who is engaging with it and how. She engages with absences, gaps and lacks through her belief that 'the gaps in records are not flaws in the archive, but rather the key to its organization. The Index begins in the gaps where language ends; that is, in the records of absence and absence of records where official language fails, and new languages must be developed in its place’ (Ghani, 2004). Her resistance involves preserving and presenting the ‘traces of redactions and erasures in the official record’ (Ghani, 2004) and pairing them with ‘witnesses of the histories it explores’ (Ghani, 2004) in order to present a counter-narrative which captures that which lies outside of institutional archives.

Figure 5. & 6. Index of the Disappeared: Parasitic Archive and Index of the Disappeared: Secrets Told (Ghani, ongoing since 2004)

Through Mnemosyne and ‘Index of the Disappeared’, Akomfrah and Ghani demonstrate how creative practice can help us explore and unpack the absences, gaps and lacks that exist These outcomes provide the viewer with the space and language to think critically about what absence signifies and perhaps begin to identify and question absences, gaps and lack in other spaces too. Mnemosyne and Index of the Disappeared give us tangible, visual examples of how hyphenated individuals can resist the narratives reinforced in institutional archives which inform institutional social memory. These examples are large-scale bodies of work that involve funding, years of work, and access to archives and information beyond what is possible for most individuals. For the hyphenated individual to be able to engage in this same resistance, in the service of the construction of their own identity through the process of redefinition, they need to use memory. “Identity is extremely important for every group, particularly the marginalised who feel the need to assert a strong identity in the face of the power structures that attempt to stamp them out. Identity can be created in a vacuum of recorded memory; it can incorporate the lack, and the pressure of the absence shapes and informs the group's knowledge of itself” (Carter, 2006, p.221). Through memory, the hyphenated individual is able to produce their own constructions, just as Akomfrah constructs his from fragments in institutional archives and Ghani constructs hers by identifying and filling its absences, lacks and gaps.

Memory is a temporal space, “different from experiences, memories are those acts of mental representation by which individuals locate themselves in time and distinguish themselves from the past” (Feindt et al., 2014, p.28). The temporality of memory is one of the reasons it can better aid the hyphenated individual in their construction of new narratives that are in service of their process of redefinition, separate from the framework of classifications and dominant narratives. Its properties as a signifier allow the 'remembered' to gain independence from the context in which they stem. Remembering can never be divorced from forgetting. You cannot have one without the other, and the same can be said of silence, absences, gaps and lacks. Speech and silence, absence and presence are “dependent and defined through the other” (Carter, 2006, p.223).

Collective memory is the “dammed up force of our mysterious ancestors within us” (Olick and Robbins, 1998, p.106) and can be a vehicle for one to create a broader understanding of their identity through the exploration of shared culture and history. Records, stories, artifacts, songs, rituals and traditions are “among countless devices used in the process of transforming individual memories into collective remembering” (Millar, 2006, p.119). They are touchstones, traces of the past, used to shape memories into narratives and transform information. However, with anything that can bring about more understanding and compassion about those who are 'other' to us, the same construct can be used to widen that gap. Within the various devices used in this process of transformation, there are ones that are sometimes discounted and their value questioned. Generally, these questions are asked by 'privileged groups' and used to control, bureaucratise, and give power to homogenising narratives that aid in the building of empires and centralised control (Jones, 2022, p.4-5). “For the marginalised, losses abound, their collective memory is deficient, their great deeds and the stories of their persecution, as they tell it, will not survive. Those who are denied speech cannot make their experience known and thus cannot influence the course of their lives or of history” (Carter, 2006, p.220).

While collective memory as a broad concept might suffer as a result of institutional social memory bleeding into it, it reveals itself to be one limited aspect of memory, not memory itself. While collective memory can, in some cases, echo the homogenising, dominant narratives of institutional archives, specific forms of it are still useful to the hyphenated individual. Akomfrah shows us this in Mnemosyne, which tries to operate with “four varieties of memory at once: the memory of the televisual archive, a literary archive, a private one, and an imagined manual of affective recollections from the Windrush generation” (Akomfrah, Scotini and Galasso, 2016, p.32). It is Akomfrah’s exploration of collective diasporic memory (the experiences of diasporic individuals and their recollections) that is most useful as we start to look at the role of memory in resistance. Akomfrah uses shots of lone figures in frozen landscapes wearing a variety of colourful winter jackets to explore diasporic individuals’ recollections of how cold Britain was, how bright their clothes were in comparison to the locals, and how solitary and lonely their arrival felt (Akomfrah, Scotini and Galasso, 2016, p.33-34). This is an experience that immigrants, regardless of how they arrived, share. In my own research, collecting recollections of immigrant experiences, the sentiment that, “It was cold. It was wet. People were not… uniformly nice” (A Home Away From Home, 2022) echoes the feelings that are visually expressed in Mnemosyne. These are my father’s words, his recollections of immigrating to Britain, now stored in our collective family memory.

Collective family memory is another useful place for the hyphenated individual to look to when constructing counter-narratives. The family archive is an example of where we can see collective family memory represented in tangible form. While often used to refer to “textual, documentary, paper-based archives belonging to specific families” (Crewe et al., 2019, p.4), this definition has been broadened in contemporary study to include photographs, autobiographical objects, and stories and items made significant by memory. A focus group participant put it best: “We have got a family archive; it lurks in the loft … There are two family archives. One lurks in the head of various people” (Crewe et al., 2019, p.11). Family recollections of experiences of immigration, integration and cultural identity formation feed into the cartographical concepts of journeys, belonging, and origins and can begin to answer the question: If I am not represented in the dominant narrative, where am I represented?

Collective memory can overlap with institutional archives as places of homogenising narratives, while personal memory can work alongside alternative readings of the archive to create legitimising narratives. Personal memory is concerned with an act of remembering so that individuals can make sense of their lives and surroundings (Dijck, 2007). This act of remembering is facilitated by sensory memory, short-term memory and long-term memory. In short, these include our ability to acquire information through our senses, capture selected information and hold it for a brief time, and remember experiences, feelings and stories. Where collective memory is about 'knowing', personal memory is about 'remembering' (Millar, 2006, p.223). There is a plurality in the relationship between personal and collective memory. The two intersect but do not seamlessly align. Without this relationship, the individual would be rendered a sort of automaton, “passively obeying the interiorised collective will when disconnected from the actual thought process of any particular person” (Olick and Robbins, 1998, p.111). For the hyphenated individual, personal memory aids in their process of redefinition because it is concerned with their own construction, their own thoughts, feelings, emotions and recollections. When combined with the contextualising forces of collective diasporic memory and collective family memory, “the moment of the hyphen” can be deconstructed, and the force of the hyphen can be understood. This force can be understood as a kind of doubling; the hyphenated individual realises that they can be shaped by more than the external perceptions that frame them as 'other'; they can be shaped by their own constructions and narratives. More than this, they now have various methods by which to do so.

Chapter 3 - Identity under construction

“In the World through which I travel, I am endlessly creating myself.” - Frantz Fanon

For the hyphenated individual, the construction of identity and the development of their concept of self brings about the beginnings of one's own claim on the past (Akomfrah, Scotini and Galasso, 2016, p.28). Rather than having to come to terms with or adopt homogenising narratives, the hyphenated individual can engage with a “continuous flow of change (self) which includes and integrates its stationary pauses (identities)” (Andacht and Michel, 2005, p.65). It is through the knowledge that institutional archives are spaces which reinforce dominant narratives, and the realisation that institutional social memory reflects a reading of the institutional archive which serves dominant groups, that creates the opportunity for resistance. This resistance is realised through the ability to read between the lines, create counter-narratives and use memory, both personal memory and various forms of collective memory, to engage in a process of redefinition.

This redefinition is a culmination of these elements, just as the self is a culmination. “To be a self is to be in process of becoming a self’; self-realisation is ‘defined by its communicative practices, oriented toward an understanding of itself in its discourse, its action, its being with others, and its experience of transcendence” (Andacht and Michel, 2005, p.57). These alternate perspectives start to break down the systems of classification that we are trapped by, demonstrating that “we are neither the passive recipients of social signs nor the omnipotent creators of meaning, but beings who are actively engaged in the universal process of meaning generation” (Andacht and Michel, 2005, p.73).

The disjuncture between the dominant narratives communicated through institutional social memory and the narratives reconstructed by the hyphenated individual through partial and perspective-based fragments found in personal, collective family and collective diasporic memory, mirrors identity construction. Identity must be considered outside fixed terms; “instead of thinking of identity as an already accomplished fact, we should think instead of identity as a 'production', which is never complete, always in process, and always constituted within, not outside, representation” (Hall and Morley, 2019, p.1). For the hyphenated individual, any sense of identity that evolves from institutional archives emerges “out of something far too generalised to be personal” (Akomfrah, Scotini and Galasso, 2016, p.26) because it is marred by a narrative and structure that is the antithesis of identity itself. The structural limitations of institutional archives contradict the evolving nature of identity, especially for those navigating multiple cultural and historical spheres. The counter-cartography produced through an alternative reading of the institutional archive is constantly evolving. This mirrors the active process of identification that responds to points of difference and is therefore always evolving through “a continuous play of history, culture and power” (Hall and Morley, 2019, p.1).

Cultural identity works in two ways in the construction of identity: “it mediates reflection on the attributes or relationships that are felt to characterise a self; simultaneously, culture works to permit individuals to index their social position by marking solidarity with a community” (Shaw, 1994, p.84). Cultural identity and collective memory are two sides of the same coin; both are systems which create a sense of oneness between those who share similarities. For the hyphenated individual, collective memory can connect them to a wider narrative of cultural identity. However, as a result of the entanglement of collective memory and the institutional archive, there are limitations to this narrative; the narrative is often co-opted by 'privileged groups', used as a method of othering, or simply erased. Personal identity is ‘many-voiced’, “constituted by a heterogeneous multiplicity” and more closely informs the idea of the self (Andacht and Michel, 2005, p.52). “It is not a distinctive trait or even a collection of traits possessed by the individual. It is the self as reflexively understood by the person in terms of her or his biography” (Andacht and Michel, 2005, p.53).

An individual with a singular racial identity might view the construction of identity and the self differently to the hyphenated individual. If a box or category has always existed for them and it has been comfortable, they will not have had to construct their sense of identity and concept of self in the same way the hyphenated individual has had to. The hyphenated individual has already had to engage with processes of reconstruction and redefinition when it comes to institutional archives and memory, and these same processes are necessary when they construct their sense of identity and concept of self. Through these processes of reconstruction and redefinition, the hyphenated individual sees absences, gaps, and lacks as indicators of presence rather than deficits.

“Absence and silence mark lack of neither language nor identity. Rather, it is a form of communication that those who rely on the hegemonic word of private authority cannot hear. The marginalised do not conform to the enunciative formations and are therefore free to speak as they wish, but with the recognition that they will have little impact on the power structures and on the discourse” (Carter, 2006, p.229).

Instead, their power lies in the ability to engage with this process of redefinition and resist the dominant narratives that marginalise them. Poet M. NourbeSe Philip wrote:

“I writing my own silence…and if you cannot ensure that your words will be taken in the way you want them to be – if you sure those you talking to not listening, or not going to understand your words, or not interested in what you are saying, and wanting to silence you, then holding on to your silence is more than a state of nonsubmission. It is resisting” (Carter, 2006, p.230).

The construction of identity and the self for the hyphenated individual goes hand in hand with the recognition that marginalised voices will not be heard by institutional archives. Even when voiced, they will be silenced. Regardless of the time the hyphenated individual takes to redefine themselves, construct their own identity and discover their concept of self, they will never be able to escape the prison of perception. In many ways, none of us can – we exist outside of ourselves through the perceptions of others, and from these perceptions, judgements are made, and opinions are formed. However, for the hyphenated individual, their 'outsides' are vague and ambiguous, misaligned from any one perception another might have of them. The way they feel about how they embody the multitudes within them will never be understood. While we all contain multitudes, the hyphenated individual contains multitudinous histories, cultures, and heritages. They exist in a space that is not represented, not widely understood, and therefore not widely accepted. However, the fact that you might not be heard or understood is not a good enough reason not to amplify your voice and wear your misunderstood identities proudly. While the hyphenated individual has very little agency when it comes to their representation within the archive, this should not limit their expression. Similarly, they are limited in any action they can take to change others’ perceptions, but this should not limit their capacity for enunciation. Expression and enunciation are internal forms of agency that the hyphenated individual has access to, forms of resistance. For the hyphenated individual, this resistance feeds the self. A self that is ever shifting and constantly under construction. This self is not simply the sum of parts but is instead formed by the way the parts relate to the whole and the way those parts materialise in the world.

Akomfrah lets an element of his identity and self-materialise in Mnemosyne by bringing in the personal and allowing it to inform the very structure of the film through his love of jazz. He focused on process and improvisation when creating Mnemosyne and was inspired by music. He said in an interview that his inspiration was “the jazz of the mid-to-late 1960s and some of those figures who I've obsessed with and worried with and loved, from late Miles Davis through Cecil Taylor and Ornette Coleman. That whole thing is obviously an inspiration, but so is classical Indian music, especially dhrupad, the idea that the point is not to arrive at a note but to take any note as the point of departure” (Budzinski, 2012). In many ways, it is unavoidable for the artist to come through in their work, but Akomfrah not only allows himself to come through but also sees the strength of evoking the personal in his work. On documentary, he said that it 'is exactly like the symphony when Schoenberg and that crowd encountered it... It was completely ossified, formulaic. [It has] this almost fossil-like symphony structure to it’ (Budzinski, 2012). In Mnemosyne, he subverts formulaic documentary style, instead calling the piece a ‘tone poem’, an allegory for the experience of post-war immigrants and hyphenated individuals which reflects the blues aesthetic – “none of it is on the note, none of it is on the beat, but you kind of garner from it what's going on” (Budzinski, 2012). Through this subversion and an introduction of an atypical structure, Akomfrah feels that he has found the “thing that propels his work forward: this is the stuff, this is where we're at, that's what we've got, let's go. Because committing to the process was actually much more interesting than just worrying about whether you've got the right score” (Budzinski, 2012).

Akomfrah’s language around how he structured Mnemosyne mirrors the continuous flow of change (self), which includes and integrates its stationary pauses (identities), the same kinds that the hyphenated individual engages with. The idea of “committing to the process” rather than worrying about “the right score” speaks to the importance of the process of constructing one’s concept of self over actually becoming a “steadfast self” (Andacht and Michel, 2005, p.57). The idea that any note should be taken “as a point of departure” rather than focusing on “arriving at that note”, speaks to the idea that while the hyphenated individual may recognise that their voice may not be heard or they might not be seen, it is still vital that they form their own voice and nurture their concept of identity and self. Marginalisation, lack of representation and the reinforcement of dominant narratives cannot be remedied by the few, and an attempt to do so will only serve to make the individual feel powerless. Personal power needs to be exercised – just as personal memory is exercised in the resistance of dominant narratives in institutional social memory. While the hyphenated individual may remain unheard by institutional spaces, the absences, gaps, and lacks can be embraced through the processes of resistance, reconstruction, and redefinition. The absences, gaps, and lacks highlight their very presence. While they may be omitted, they can never be fully erased.

Conclusion

This exploration has attempted to unpack the complexities of the construction of identity and the self, in the face of marginalisation, within the context of the hyphenated individual. This marginalisation has been explored through systems of classification, institutional archives, and institutional social memory. These systems and spaces reinforce dominant narratives which erase and omit the experiences and existence of hyphenated individuals. Alternative readings of institutional archives and the formation of new narratives through the lens of personal memory, collective family memory and collective diasporic memory give the hyphenated individual methods through which to resist this reinforcement. Through resistance, reconstruction and redefinition, the hyphenated individual is able to engage with a process of self-realisation and develop a sense of identity and concept of self on their own terms and through their own construction.

While research-based, this essay has been influenced by my personal experiences as a hyphenated individual. I have learnt a lot through this exploration and hope that it can provide you, the reader, with a better understanding of the hyphenated individual but also inform how you view yourself and the structures we live within. I don't believe anyone has a 'fixed' identity and concept of self, and I hope that even individuals with a singular racial or cultural identity can see, through this exploration, that the lines we draw to differentiate between ‘you’ and ‘me’, ‘us’ and ‘them’, are just as dynamic and changeable as we are. This exploration has provided me with an appreciation for the absences, gaps and lacks I am shaped around and embody. When identified, they speak to our unwillingness to be erased or forgotten, signifying our presence.

The process of writing this essay has inevitably raised questions that are beyond the scope of this exploration. What other insights can be drawn from engaging with the experiences of marginalised people? Where else do we find absences, gaps, and lacks that speak to a hidden presence? What is the role of creative practice in answering, interrogating, or shedding light on the themes and concepts explored in this essay?

I can begin to answer that last question. In short, the process of engaging with these themes and concepts through creative practice makes the ‘political’ more accessible through the evocation of the ‘personal’. Mnemosyne and Index of the Disappeared, gave me some much-needed grounding as I conducted this exploration, which, without these visual examples and applications of the key concepts, was very conceptual and, as a result, difficult to unpack. These works do not simply provide a visualisation; they speak to the individual, ask for their engagement and provide the language for further exploration. Finding more artists, practitioners, filmmakers, and so on who explore archives, memory, diaspora, and the 'Other' in their work is a key point of interest for me as I continue to try to make sense of the mess.

Bibliography

Akomfrah, J., Scotini, M. and Galasso, E. (2016) ‘Memory and the Morphologies of Difference’, in Politics of Memory: Documentary and Archive.

Andacht, F. & Michel, M. (2005). A Semiotic Reflection on Self-interpretation and Identity. Theory & Psychology, 15(1).

Andrés Manuel Cáceres Barbosa and Cristina Voto. (2021) ‘Archive, Practices, and Memory Policies’, Signata [Online].

Budzinski, N. (2012) John Akomfrah: The Nine Muses, The Wire. (Accessed: 03 December 2023).

Carter, Rodney G.S. (2006) ‘Of Things Said and Unsaid: Power, Archival Silences, and Power in Silence’. Archivaria 61.

Crewe, V.A. et al. (2019) We are what we keep: The "family archive", identity and public/private heritage. Heritage and Society, 10 (3). pp. 203-220.

Dijck, J. van (2007) Mediated Memories in the Digital Age. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Feindt, G. et al. (2014) ‘Entangled memory: Toward a Third Wave in Memory Studies’, History and Theory, 53(1).

Hall, S. (1997) ‘Race the Floating Signifier’.

Hall, S. and Morley, D. (2019) Essential Essays, Volume 2: Identity and Diaspora. Duke University Press.

Harris, W. (2018) Mixed-race Superman: Keanu, Obama, and multiracial experience.

Hedstrom, M. (2002) ‘Archives, Memory, and Interfaces with the Past’.

Jones, Mason A. (2022) ‘Selective Memory: Assessing Conventions of Memory in the Archival Literature’. Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies: Vol. 9, Article 1.

Kainz, L. (2016) People Can’t Flood, Flow or Stream: Diverting Dominant Media Discourses on Migration. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2016/02/people-can’t (Accessed: 03 December 2023).

Krook, M.L. (2020) Violence Against Women in Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Map Marathon 2010 – Mnemosyne (2016). Serpentine Galleries. 14 January. (Accessed: 03 December 2023).

Millar, L. (2006) ‘Touchstones: Considering the Relationship Between Memory and Archives’. Archivaria 61, 105-26.

Mnemosyne (no date) Smoking Dogs Films. (Accessed: 03 December 2023).

Olick, J.K. and Robbins, J. (1998) ‘Social Memory Studies: From “Collective Memory” to the Historical Sociology of Mnemonic Practices’, Annual Review of Sociology, 24(1), 105–140.

Shaw, T. A. (1994). ‘The Semiotic Mediation of Identity’. Ethos, 22(1).

Figures

Figures 1 & 2

Mnemosyne (2010).

Figure 3

Census 2021 - England & Wales (2019) Twitter. Available at: https://twitter.com/Census2021/status/1202208431718969347.

Figure 4

Laux, R. (2019) ‘50 years of collecting ethnicity data’, History of government, 7 March. Available at: https://history.blog.gov.uk/2019/03/07/50-years-of-collecting-ethnicity-data/.

Figures 5 & 6

Index of the Disappeared (ongoing) MARIAM GHANI. Available at: https://www.mariamghani.com/work/626#:~:text=As an archive%2C Index of,intelligence interventions around the world. (Accessed: 15 December 2023).