How Does Visual Art Challenge, Reflect, and Shape the Ostalgic Identity

“Things that were hard to bear are sweet to remember." – Seneca

The twentieth century in Eastern Europe began with utopia and ended with nostalgia. Future optimism was easily forgotten, whereas nostalgia remained eerily modern and, for better or worse, never went out of style. The Greek words “nostos”, which means “return home”, and “algia”, in the sense of “longing”, are the roots of the compound “nos-talgia”. Svetlana Boym, visual artist and professor of Slavic literature at Harvard University characterized it as a yearning for home that is either no longer there or even worse - never was. The emotion is one of loss and dislocation/disconnection, yet it can often cause romance with one's own fantasies. That “nostalgia” which I will use as the basis of my paper is more of a historical, even national feeling rather than just a personal illness:

“Ostalgia” (Ost [ɔst] - East in German) / nostalgia for communist times) – is a widespread phenomenon in all of the countries of the former Eastern bloc. It comes in numerous forms, such as reviving favourite communist TV shows and films, collecting old prints, postmarks and even everyday objects inspired by the soviet design. But should we look at the feeling of “ostalgia” as a harmless hobby, a simple expression of sentiment, or does it serve as a portrayal of a more complex matter - the “terra incognita” of the collective memory?

Different studies have delved into the phenomenon of ostalgia across various fields such as culture, politics, and sociology. However, within the realm of visual arts, this subject remains underrepresented and warrants further exploration. How does the visual expression of this phenomenon shape, distort, or confront the historical narrative? Can art, produced during soviet time serve as an alternative archive, a domain for resurrecting memories erased by the regime’s censorship and manipulation? In this research, nostalgia is being examined not only as a tool for “political lobotomy” (referring to Robert Smithson’s words which he used to describe mass consumed art) but also as a reinforcer of national delusions. But to truly grasp its concept, one must look to the present, not the past. Similar occurrences might be seen in the context we live in today, although vastly different in ideological underpinnings. While the repressive elements of communist regimes stifled dissent through censorship and political control, today’s societal structure presents a different yet equally potent narrative of authority and influence. In both systems, nostalgia can operate as a response to unmet expectations and uncertainties, reinforcing societal narratives that may obscure complexities and injustices. Recognizing these distinct realizations of repressive mechanisms is crucial for a nuanced understanding of the multifaceted impacts of the nostalgic sentiment. The intensity of nostalgic emotions is intricately linked to the condition of society - in simpler terms, the more a society grapples with unmet expectations and unfulfilled hopes, the more pronounced its absorption into nostalgia becomes (Štroblová, 2020):

“Nostalgia itself has a utopian dimension, only it is no longer directed toward the future. Sometimes is not directed toward the past either, but rather sideways. The nostalgic feels stiffled within the conventional confines of time and space.” (Boym, 2001)

Lost in Time

Through a distortion of reality, nostalgia idealizes its object in a particular way, locates it in a time of great purity and innocence. Therefore, it has the potential to alter reality in ethically concerning ways (Margalit, 2011). While some forms lightly distort, akin to retouching a photograph to appear slightly younger, the phenomenon of ostalgia is a more profound distortion where the unpleasant aspects of the Communist Bloc and party comrades are erased, leaving behind an idealized sense of a close-knit community, untainted by the complexities of historical reality. While the first, in its primary sense, is internally related to first-hand memories, ostalgia is more of a collective experience and therefore is able to forge the past on a greater scale. It could be seen as a selective and idealized reconstruction of the past, manifesting as a desire to rebuild a romanticized version of what is perceived as a simpler, more harmonious era. This is not a passive remembrance but an active engagement in forging memories that align with a desired narrative (Boym, 2001). It descends into idealization, where the complex realities of the past are simplified and romanticized. In "Defense of Lost Causes," Slavoj Žižek explores why individuals might be drawn to regimes known for oppression and catastrophe - not because they desire oppression, but because these regimes represent unrealized potentials. Longing, as a feeling, implies the existence of alternative paths and futures beyond the dominant narratives (Žižek, 2008). At a broader societal level, ostalgia plays a pivotal role in shaping collective memories and historical discourses. It contributes to the creation of cultural myths and idealised national narratives, often overlooking nuances and complexities. This selective idealisation has profound implications, influencing not only how a society perceives its past but also shaping its present identity and future aspirations. It emerges as a powerful force able to “colorize” memories while also contributing to the ongoing construction of a shared historical identity.

Nostalgia Entrepreneurs

This common memorialization “strategy” is seen in all post-soviet countries, standing as a crucial axis around which my research emerges. These nation's experiences, perceptions, and recollection are profoundly shaped by the seismic shifts that swept through the region during their formative years. Generation after generation caught in a transitional space, between the echoes of the history and the uncertainties of the future. Now these nations are offered an altered version of their past, once again, through a transnational memory of the regime focusing on the „retro-aesthetics” of communism, rather than its disrupting essence. A good example of this would be the hundreds of daily life museums of communism that are used as aestheticization of the soviet culture in recent years. These “nostalgia entrepreneurs” (“The Museum of the Communist Consumer” in Bucharest, Romania, „Museum of Communism” in the Czech Republic, “Retro Museum” in Bulgaria and “PRL Museum” in Poland) use objects of the daily life during communism to reconstruct an affective, personalized version of the history for the citizens of the ex-communist countries, emphasizing solely on the positive aspects.

One illustrative example is The Museum of Communism in Garvan village, based in Northeastern Bulgaria. The museum is an attempt for institutionalizing ostalgia - without offering a complete image of the totalitarian history, the space is recalling only desirable details from the recent past; in this sense, it provides a viewpoint that is closer to a utopian vision than a critical debate (Pancheva-Kirkova, 2013). The exhibition commences with the inclusion of the coat of arms, two maps depicting Bulgaria, and a prominently displayed portrait of Todor Zhivkov (General Secretary of the Bulgarian Communist Party, he was the second longest-serving Eastern Bloc leader). These elements serve as symbols that establish the connection between the remembrance of Communism and the notion of “national identity”. The exhibition proceeds to sequentially highlight the various aspects of life under Communism - within one of the halls, visitors can observe artefacts related to school life, such as pioneer ties, school uniforms, and textbooks. Additionally, there are objects dedicated to the youth, including photographs of individuals from rural areas during their time as students, as well as portraits of prominent young Communists who met their death during the revolution. The subsequent room showcases items associated with the next logical phase of life under Communism – the membership in the party, represented through the display of comrade cards and scenarios for prosperity (M.O.C, 2014).

Within the exhibition, there is an absence of any sense of constraint, rather a feeling of harmony, solidarity and unity is convincingly being portrayed. It serves as a first-hand example of how the ostalgic memory is exploited to selectively erase any ‘unpleasant’, or maybe a better word would be ‘unnecessary’ aspects of the Communist era, creating an inviting and cosy atmosphere that deludes the past in utopian depiction of life.

Who are we?

This manipulation of ostalgia towards the Soviet era could be traced back to the 1990s and early 2000s creating a selective historical narrative, neutralizing the “rotten” side of Soviet history and establishing a continuity between past and present. Gradually ostalgia started to be used as a sociological weapon, “a state of mind” (Shaw & Chase, 1989), forming the basis of the Eastern European identity and the permanent delusion of generations. It is not just the desire for unrealized safety, stability, and prosperity; it is also the "forced" sense of loss in the absence of a very particular kind of sociability, and even the vulgarization of cultural life. It is the desire of those who have experienced communism to infuse their lives with purpose and honour, and not be regarded, remembered, or pitied as failures, losers or slaves in the eyes of the public (Maria Todorova, 2012). As Todorova writes in “Post-Communist Nostalgia”, the term becomes relevant only when there is no possibility of returning and when progress is noticeable. It signifies a critical juncture, where there is still a lived experience but little optimism or even inclination to go back due to a depletion of choices and a glimmer of hope for what lies ahead. It is the disadvantaged who feel ostalgic but the ostalgia is triggered by their recognition of the inevitabilities of the present (Creed, 2010). But even the ones who have reached this realization are well-aware that the ostalgic principles are now deeply established in our nature. As Teofil Pančić, Serbian literary critic, often attacked for his fiercely anti-nationalist political stance, states in Lexicon of YU (Yugoslavian) Mythology:

“Whether we call it ostalgia or not, we have the right to keep our memories of socialism, since they are proof that everything from our past that we remember so well was not a dream or an imagination, a proof that we were and remained somewhere and someone.”

The Ex-People

Now only in the realm of memory, people from the Eastern Bloc find solace in recapturing their feelings of security and autonomy and fill the social and historical void left by the collapse of totalitarian states. Or can they look somewhere else to seek the truth and be reminded? Can we look at visual art as an alternative archive, a domain for erased memories? Would visual artists, considered to be escapist, be able to expose these fractured but so romanticized parts of life before 1989 to the people who out of instinct, believe it to be better than the chaos and decay of modern life? As the English painter and art critic John Berger, a close associate of the Communist Party of Great Britain, argues in “Art and Revolution”: their artwork serves as a reminder, or maybe a predictor that ostlagia is not the desire to return to communist time rather a fruitless dream to recapture what life was promised to be at that time (1998). Like a defence mechanism, that treats its own narrative as the absolute truth, protected at all cost. Now this historical fiction is spreading through generations and could be seen as a rising interest among the youngest, evoking secondhand ostalgia even in those who did not experience the past directly. Visually rooted in our childhood, memories, museums, movies and material culture, now the ostalgia trend can be seen all around the present– still rejecting the globalized world and censoring reality. It’s a vague promise for discovering one’s self. This phenomenon is well illustrated by the designer and visual artist Douglas Coupland (1991) by the name “legislated nostalgia”. In his novel “Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture” he states that the majority of the generation's time is spent thinking backwards. Whether you remember it or not, participation is mandatory - “legislated nostalgia - to force a body of people to have memories they do not actually possess”.

Censorship of Memory

And this is how the surreal world of the post-Soviet emerged – through censorship of memory. But censorship was way too formidable tool not to be recognized for its ability to control the bigger narrative, so it started wielding its influence across various dimensions of societal expression. Ostalgia and false sentiment wouldn’t be enough to maintain the “squeaky clean” past so the censorship worked its way up to all parts of the public domain – newspapers, magazines, foreign books and journals, all types of political propaganda employed deliberate strategies to alter and re-design reality. “The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin's Russia" by the graphic designer David King stands as a haunting portrayal of the orchestrated manipulation and multilayered propaganda that defined the Soviet era. This in-depth investigation reveals the regime’s meticulous efforts to revisit history, where airbrushing and altering photographs became powerful instruments for shaping public perceptions and, naturally – collective memory (McCrystal, 2017). The London-based magazine “Index” (previously known as “Index on Censorship”), whose launch in 1972 was directly sparked by the levels of state censorship and repression of artists in the Soviet Union, voiced that the act of erasing individuals from official photographs, once prominent figures labelled as "enemies of the people" transcended mere historical revisionism. It is now seen as a calculated effort to re-design history, expunging dissent and opposition from the visual narrative. The regime early on recognized the influence of visual representation on public consciousness, thus the removal of dissenting voices from official photographs aimed not only to alter the historical record but also to obliterate any trace of opposition to “the prescribed ideological path” (Censorship, 2017).

In his work David King meticulously dissects these visual alterations, presenting a gallery of juxtaposed images that starkly reveal the before-and-after effects of the regime's airbrushing campaigns. The photographs, initially innocuous depictions of political events, metamorphose into haunting symbols of state-sponsored manipulation. These fabricated photographs were not confined to government offices but disseminated widely, becoming embedded in the public consciousness. They served as potent tools to reinforce the regime's narrative, presenting a sanitized version of history aligned with the prevailing political agenda. His work underscores the extent to which the Soviet alterations went to control public perception, challenging viewers to question even further the authenticity of their memories.

The Dissidents

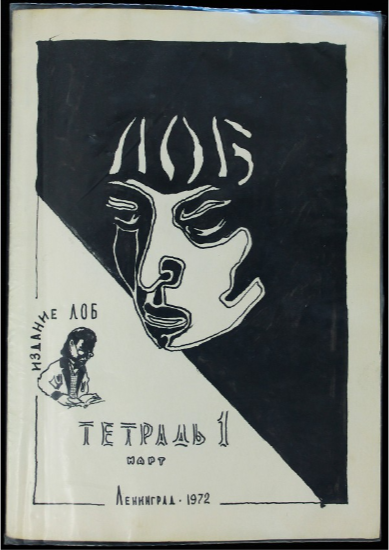

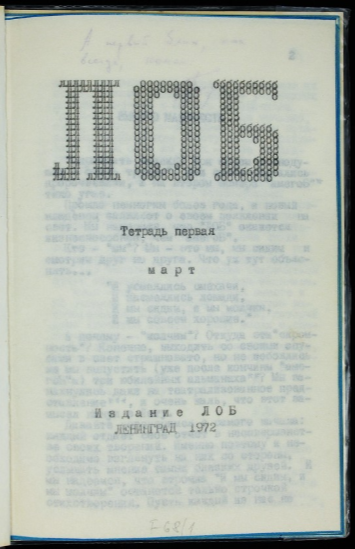

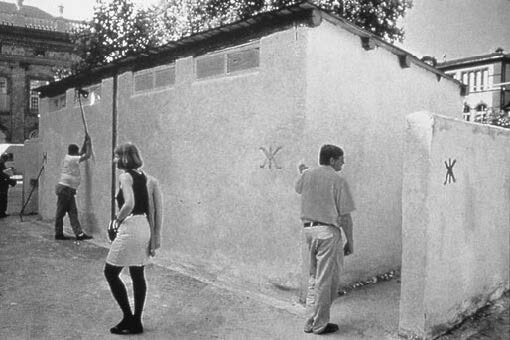

But naturally, where is oppression, there is a revolution - faced with the state's powers of censorship, society turned to underground art and literature for self-analysis and self-expression. In recognition of the word, being highly relevant in the Soviet context, the definition of a "dissident" was changed in 1993 by the New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary to read, "A person who openly opposes the policies of a totalitarian (esp. Communist) régime". But back in the days, being dissident simply meant taking an intellectual stand. And naturally, in all fields of art and culture a stand was made. The “samizdat” (self-published, self-distributed) movement has emerged and used throughout the Soviet Union where people copied clandestine, banned publications by hand and distributed them from reader to reader (Figure 1.) Due to the official registration and access requirements for typewriters and printing machines, manual replication was a common practice.

Figure 1. The first issue of ЛОБ (Forehead), 1972. / ЛОБ was produced by a group of students from the Chemistry Department at Leningrad State University, under the leadership of Sergei Dediulin and Vitaly Petranovsky.

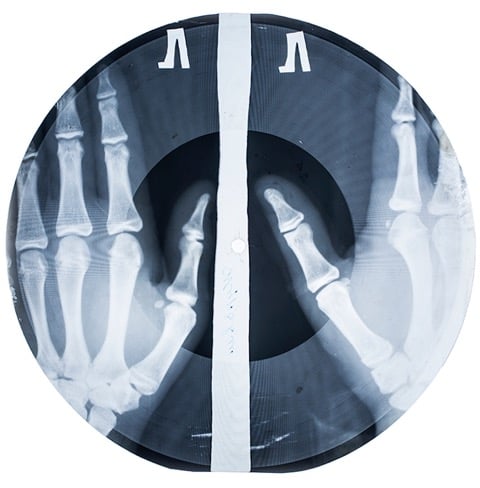

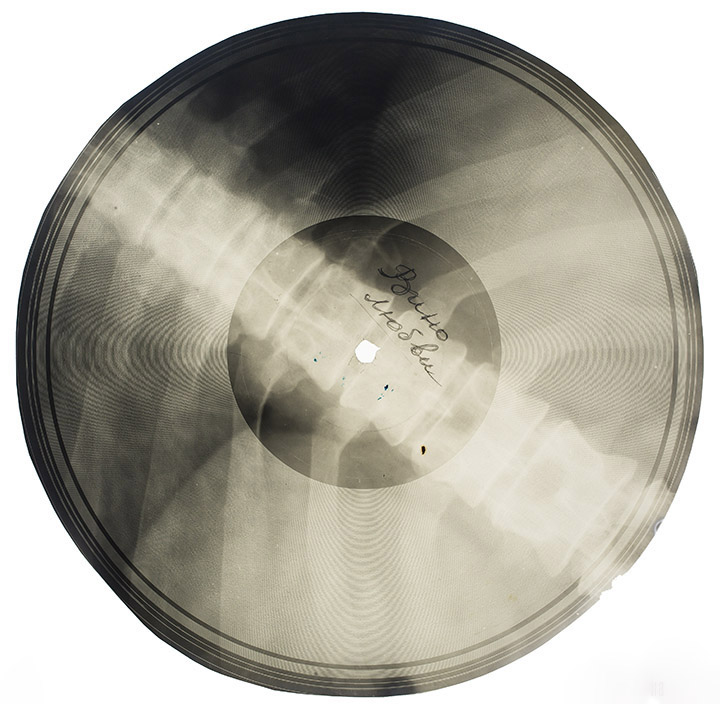

Figure 2. Examples of Bone Records / Courtesy of The Bureau of Lost Culture - Stephen Coates and Paul Heartfield, 2019.

But out of all forms of cultural resistance, visual art stood out as the most potent catalyst for revolution. In the oppressive landscape of the Soviet Union, the censorship of art reached drastic extremes. The government's unwavering commitment to socialist realism as the sole sanctioned artistic doctrine meant that any deviation from this style was met with severe consequences. In a conversation with the filmmaker and art critic Amai Wallach, Erik Bulatov – one of the giants of contemporary art shared: “If you wanted to be a painter, you painted Lenin and Stalin, If pictures were what interested you, there was very little other than Lenin, Stalin, and heroes of the Revolution to look at. Certainly no Malevich or Chagall. But no Matisse, either, no Monet, Renoir, or Cezanne. Van Gogh and Gauguin were called degenerates and charlatans, if not mad” (Wallach, 1991). The new society could not accept academics, Jews, or artists who were dangerously skilled in objectivity and creative expression (Kabakov, 1987). The artist assumed the role of either a collaborator in this deception and censorship or an enemy of the state who needed to be destroyed - the sole purpose of the mainstream art was to promote blind adoration through the use of altarpieces featuring heroes of the people to elicit actions of devotion. In response to these stifling conditions, a clandestine underground art scene emerged. Dissident artists operated in the shadows, organizing secret exhibitions to showcase their work beyond the reach of official scrutiny. These exhibitions became subversive havens, allowing artists to express their truth, experiment with diverse styles, and challenge the ideological foundations of the regime. The alternative archive of memory emerged.

While the personal ostalgia and political propaganda construct a selective version of history, art produced during these tumultuous times acts as a counterbalance. Artists take on the role of guardians of collective memory, holding onto the nuance and lived experiences that others would prefer to be forgotten. Their work became the instrument of resistance, reclaiming silenced voices and paving the way for a more authentic reconstruction of history - one that embraces the multifaceted nature of the past. What all they share is not only a specific national identity or background, but rather an infatuation with time, both as a subject of their creativity and as a means of expression. It is certainly not a coincidence that many of the produced work is proudly, almost stubbornly analogue: there is an insistence on physical installations as the preferred medium of memory, photography, and a fascination with objects, preserving memories like time capsules. Other artists sew, mend, and stitch, almost like weaving threads of history together (Massimiliano & Jarrett, 2011).

The Ultimate Archive

Memory is a political issue for a large number of the creators in question. In "The Future of Nostalgia" (2001), Svetlana Boym noted that despite the differences in the USSR countries, there was one thing that these nations' alternative intellectual cultures had in common from the 1960s and up until today - the formation of a "counter-memory" that serves as the basis for democratic resistance. Mixing private confessions and collective traumas, the archive of visual art describes a psychological landscape of entire societies who try to negotiate new relationships to history, identity and ideology. Artists came to occupy a peculiar place in the socialist era, acting simultaneously as outcasts, visionaries, and witnesses. In his publication of essays “On Art”, a collection that fills a serious gap in the Soviet history, the Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser writes:

“Art makes us see… the ideology from which it emerges, in which it resides, from which it, being art, dissociates itself and to which it alludes.”_ (Althusser, 1984)

Prohibiting art meant indeed prohibiting the truth. It is crucial to remember that during the regime, censorship was the norm rather than the exception. While some have grown attracted to these limitations, like the artists in the West may imposed limitations on colors, materials, or mediums in an effort to challenge themselves, in the East the limits themselves started to serve as both an inspiration and a subject for art.

The Unofficials

Figure.3 The Toilets by Ilya Kabakov, Documenta IX, 13 Jun 1992 - 20 Sep 1992

Figure 4 Inside “The Toilets” Installation

Figure 5 Inside “The Toilets” Installation

Life is going on normally, almost like things have never changed. In her analysis about his work, Boym addresses that Kabakov's installations are always about the displaced past rather than being strictly site-specific. The human figures are never featured in them so that the viewer can take on the role of a protagonist in the story by experiencing the empty interiors.

Since it offers spectators the tangible opportunity to see (and, in some cases, even touch) actual things that were a part of the Soviet past, the installation appears to solve many of the challenges inherent in depicting the forgotten memories. In fact, many artists recognized and exploited the installation medium’s unique potential, utilizing it as a powerful tool to encapsulate the intricate layers of the Soviet historical narrative. "Art Warehouse" by Sergej Volkov takes a similar stance toward objects and their importance as potential storytellers. His 1990 installation displays dozens of items, all sealed in huge glass jars placed on a row of metal shelves, that directly evoke the Soviet era (Figure 6., Figure 7.) These jars are very similar to the ubiquitous Soviet “banki”, which contained a variety of homemade sweet and salty remedies. Volkov expands on the theme of reality/nostalgia in his 1994 piece “Dusty Models” (architectural clay, dust, glass, and wood). In her study of Post-Soviet Art and Literature, Irina Marchestini (2014) defines this installation as an intersection of metaphysics and conceptualism - a variety of dusty artefacts are displayed for preservation in a vacuum flask made of greenish laboratory glass. The objects are a collection of household and architectural items (or maybe household-architectures) like for example the Soviet-designed couch.

Figure 6, Figure 7. “Dusty Models” by Sergei Volkov, June 21 - August 20, 1994

This domestic environment aims to structure and reflect political attitudes in addition to fundamental cultural norms. By photographing and preserving the objects just before they truly disappear, the artist's "dusty technique" conveys the message of non-existent utopia, shallow promises and fraudulent memory. In this context, the role of the art assumes a quite important form: rather than offering sedatives to numb trauma ‘patients’, the artist goes to the heart of the problem, both literally and figuratively (Dickinson, 2015). He or she triggers in the post-Soviet audience feelings of contradiction and conflict about the trauma they have suffered as well as their own "sutured belief" in a reality that, despite its crudeness, serves as the foundation for their identity (Marchesini, 2014). As the Russian art critic and philosopher Boris Groys explains in his essay "The Other Gaze" (2012) the function of the "unofficial" artist in society was "to manifest his or her individual truth in the face of the official public lie". The majority of these artists believed that it was their responsibility to draw attention to the personal injustices that the communist regime had brought upon them. Being a dissident meant to break the oppression of the social realism.

Conceptualism 101

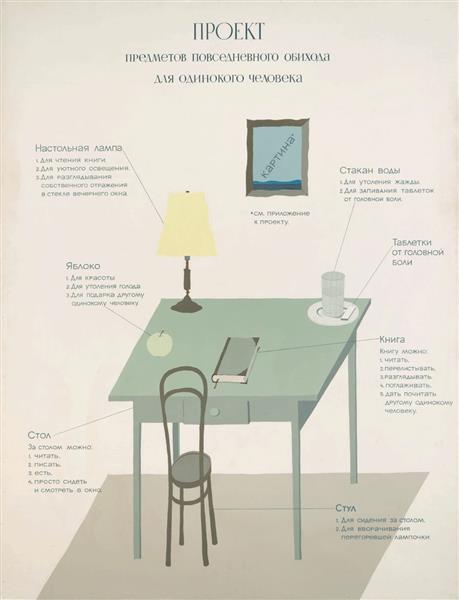

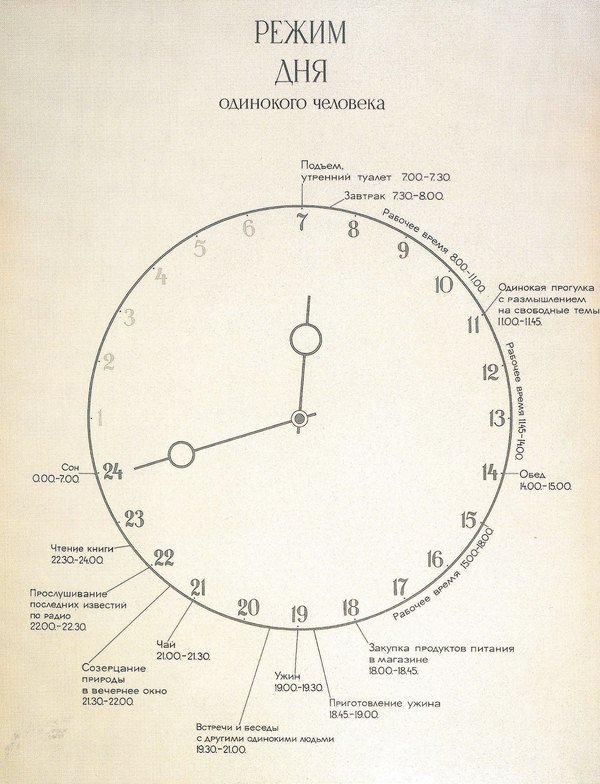

In 1979, Groys created the series “Moscow Romantic Conceptualism 101” in which he analysed the most prominent names and artworks of the movement along with their concepts such as freedom, choice, and courage in a restrictive environment and how they were presented through art. Moscow Romantic Conceptualism was a major underground art movement which emerged in the severe ideological conventionality of the Soviet Union and whose effects may still frequently be seen in the rebellious modern art. It was both a protest and a disruption of the limitations that were prevalent at the time in both the personal and artistic spheres. One of the big names that Boris Groys analyzed in his series is the one of Viktor Pivovarov, whose work critically reflected the complete “ideologization” of the Soviet lifestyle. In “The History of Culture”, Pivovarov writes, “Every so often there are periods of explosions, revolutions, years of unusual productivity and an unbelievable concentration of creative energy that artists can latch on to. And in Moscow, this occurred between the years of 1972-1976, when they did everything they could to stop it.” His preferred medium of choice was the household enamel paint on fiberboard - a reference to the Soviet Union's seemingly ad-free visual landscape on the outside, but packed with government-issued signs and posters covered with warnings and slogans on the inside. Produced by skilled graphic designers, these signs were created by hand in large quantities, however, they were designed to appear as though they were mass-produced. Pivovarov and other Moscow conceptualists took note of and explored in their own work the widespread use of stencils and templates to attain this "conveyor belt" appearance (Tate, 2015). In one of his earliest pieces, “Meditation by the Window”, these symbolism and imagery first appeared eventually becoming part of his graphic language. The concepts and metaphors from “Meditation by the Window” were later expanded in the 1975 series “Projects for a Lonely Man” (Figure 8., Figure 9.), which traced the origins of a faceless character known only simply as a "Lonely Man" in his cramped, airless surrounding. The artwork was an assembly of pages containing projects for a lonely person's life story - a version of his living area, supposed daily schedule, and even his dreams and perception of the sky - it is a biography project that aims to replicate the life of a typical Soviet citizen in many formal aspects (Groys, 1979). Even when speaking about his audience in the Soviet context, Pivovarov confirms that it consisted mostly of members of his social circle - other artists, poets, musicians, and such, but also the ones who were "hungry, in a cultural sense" (Pivovarov, 2015). His art refers to the soviet identity condition as conscious loneliness - when a person maintains an active social life which consists of aware engaging with other lonely individuals.

Figure 8. “Set of Household Items for a Lonely Man” by Viktor Pivovarov, 1975

Figure 9. “Daily Schedule for a Lonely Man” by Viktor Pivovarov, 1975

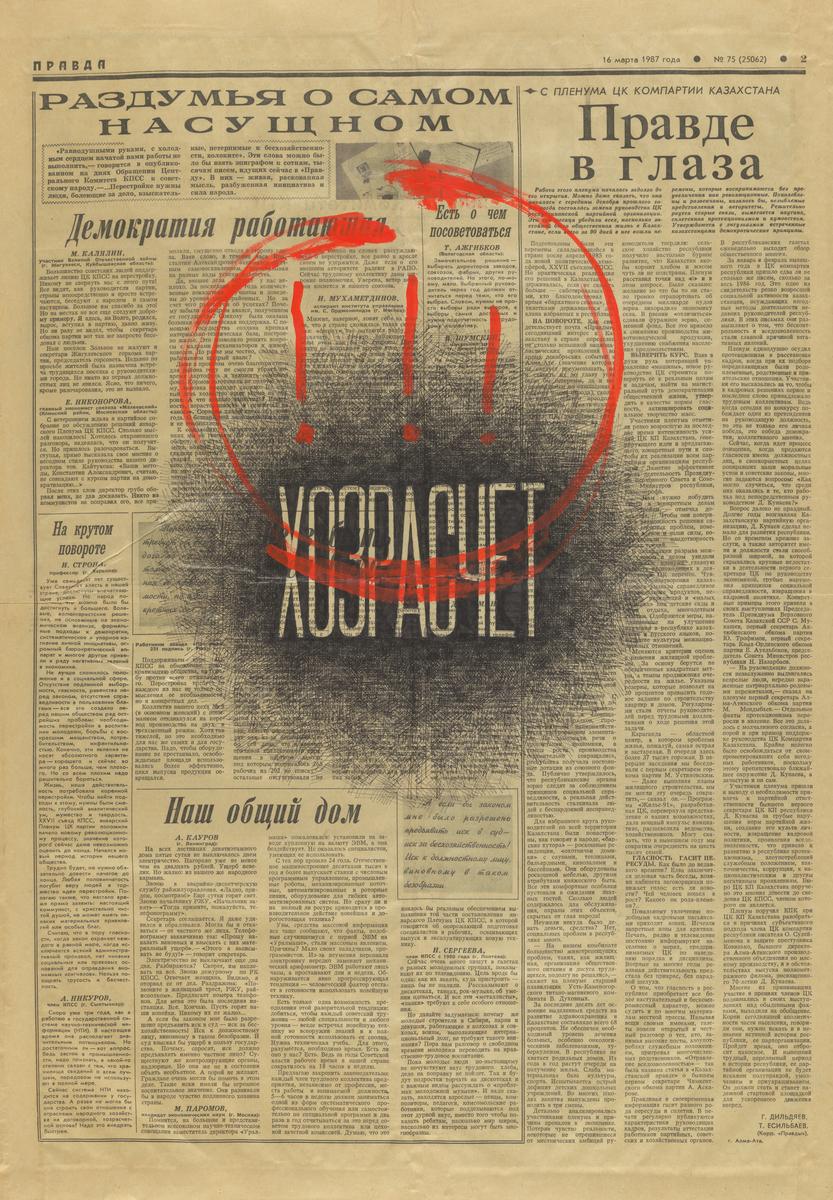

Another valuable member of the Circle 101 was Dmitri Prigov. According to Boris Groys, Prigov was “the voice and face of both the anxious instability and the vitality of perpetual movement”, he personified the nervous instability as well as the energy of constant motion that was needed for the emerge of the counter memory. In order to illustrate the antinomy of the unifying force of art and the separation of the artist, he adopted and blend of different styles and inspirations (Figure 10.) - the latter is particularly relevant because of the authoritarian environment where Prigov formed his creative vision. He belonged to the artistic society that shared an ideological opposition to government propaganda during an expected period of change, the nature of which was uncertain as the position of Soviet underground artists was precarious both then and in the future. He believed that authors had to create their own imaginary universes in which art could exist without worrying about its acceptance or comprehension (Groys, 1979). Prigov’s artwork served as a striking illustration of this unwavering, relentless creativity in the face of censorship and despair.

Figure 10. Drawings on newspapers by Dmitri Prigov, 1970

Moscow Conceptualism aimed to test the limits of Soviet art and censorship while also challenging the status quo of the artist as an ordinary citizen. The movement's key characteristic was the use of language, utilized to build new artistic realities. One of its famous representatives, poet and trained philologist Andrei Monastyrski, who employed language as a key medium in his performances and installations, has long been an advocate for the importance of archiving and cataloguing soviet art. In the 90s he created the MANI archive - a limited number of five MANI papki (files) that included a wide range of the underground work of artists during this period of Soviet art history, providing access to materials that would otherwise be difficult or impossible to obtain (Groys, 1979). The archive acts as a concrete protest against censorship and underscores the inextricable connection between art, memory, and opposition. The five MANI folders embody the concept that art at the time served as a resilient form of dissent against the oppressive forces of the regime as well as a timeless repository of the pure collective memory.

The Absence of Presence

By dissecting the work of artists and creators who were active during, or directly after the years of oppression is clear for one to see the importance of art’s role in preserving the archived memories of the blurry past. If questioning the ability of art, created during the Soviet era to function as an alternative repository, providing a space for reviving memories that were deliberately erased by the regime's censorship and manipulation - their work serves as the incontestable proof. In fact, art produced during that formative period stands not only as a visual reminder of the forgotten reality but as the ultimate one. In this setting, it takes on a function of utmost importance, acting as a medium for societal transcendence. These individuals’ pursuits of creativity become a source of collective memory, offering insights into the lived experiences of individuals and communities during a time marked by political control and ideological constraints. Their artistic expression demonstrates how art may serve as a transformative escape, providing society with the tools it needs to break free from its limitations and enter the new mindset. The artistic medium, whether in the form of paintings, installations, performances, or other visual expressions, provides a unique lens through which to explore and understand the complexities of Soviet history. These artworks act as visual testimonies, capturing the emotions, struggles, and aspirations of individuals living in a society marked by censorship and political repression. In essence, they become a testament to the resilience of the dissident spirit and the power of artistic expression in the face of the highest restraint. Now their work serves as the implicit testimony to the power of the visual as a catalyst for social change, a source of reality and most importantly - domain of memory.

Nowadays this message is being inherited and distributed by the new age artists, using almost the same stubbornly analogue techniques that reflect on these limitations – both then and now. Because despite the fact that the Soviet Union fell apart almost twenty years ago, the societies and cultures of Eastern Europe remain reliant on its Soviet heritage. Our past is being simultaneously defended and rejected in almost every aspect of symbolic production: from elite literature to mass art, from political ideology to community beliefs. The Soviet society is stuck in time - between its cultural legacy, whose models are no longer relevant, and its historical myths whose manipulated narratives will forever be cherished and aestheticized.

The present-day Eastern European artists continue to revolve around the past, still searching for the missing pieces of the collective memory as well as the politically altered or untold truths. Being born in a time characterized by changing attitudes towards the Soviet narrative, the current artistic perception possesses a unique position towards the ostalgia-driven reflections which is seen in almost every aspect of our cultural concept and offers valuable insight into the dynamics of societal change, memory, and identity. In the work of the new generation artists, the process of reconstruction and re-creation of the soviet times is to this day still being witnessed, communicating the same message of disruption of the recent past. Its reflection didn’t fade out through the years of “active forgetting”, overpowered by the government manipulations and censorship. And despite being overlooked and hardly acknowledged in the Western world, the artistic movement in Eastern Europe is until today seeking for the covered truths. Because it has the obligation to remember.

Bibliography

Althusser, L., 1984. Essays on Ideology.. 1st ed. s.l.:Verso.

Anon., 1991. Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture. s.l.:St. Martin's Press.

Anon., n.d. s.l.: s.n.

Boyer, D., 2010. From Algos to Autonomos: Nostalgic Eastern Europe as Postimperial Mania, s.l.: s.n.

Boym, S., 1998. On Diasporic Intimacy: Ilya Kabakov's Installations and Immigrant Homes. Critical Inquiry, 24(2), pp. 498-524.

Boym, S., 2001. The Future of Nostalgia. 2nd ed. New York: Basic Books.

Boym, S., 2001. The Future of Nostalgia. 1st ed. s.l.:Basic Books.

Boym, S., 2010. Nostalgia and Its Dicontents. [Online]

Available at: https://www.scribd.com/doc/163147985/Svetlana-Boym-Nostalgia-and-Its-Dicontents

[Accessed 2 09 2023].

Censorship, I. O., 2017. Index On Censorship. [Online]

Available at: https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/08/commissar-vanishes/

[Accessed 11 11 2023].

Creed, G. W., 2010. Strange Bedfellows: Socialist Nostalgia and Neoliberalism in Bulgaria, s.l.: s.n.

Dickinson, S., 2015. Melancholic Identities, Toska and Reflective Nostalgia. s.l.:University Press.

Groys, B., 1979. The Celebration of Solitude. Moscow Romantic Conceptualism 101.

Groys, B., 1979. The Cultural Labour. Moscow Romantic Conceptualism 101.

Groys, B., 1979. The Resurrection of Romanticism. Moscow Romantic Conceptualism 101.

Groys, B., 2012. The Other Gaze. Under the Gaze of Theory, Issue 35.

Kabakov, I., 1987. Eric Bulatov and Ilya Kabakov in conversation with Claudia Jolles and Viktor Misiano [Interview] (December 1987).

King, D., 1997. Introduction. In: N. York, ed. The Commissar Vanishes. s.l.:Metropolitan Books Henry Holt and Company, pp. 8-14.

La Grande Bellezza. 2013. [Film] Directed by Paolo Sorrentino. Italy: Indigo Film.

Litvinov, G., 2009. Стиляги, как это было. s.l.:Amfora.

M.O.C, 2014. The Museum of Communism, Garvan. [Online]

Available at: https://muzejnakomunizma.com/index.html

[Accessed 4 11 2023].

Marchesini, I., 2014. The Presence of Absence. Longing and Nostalgia in Post-Soviet, s.l.: University of Bologna.

Marchesini, I., 2015. The Presence of Absence. Longing and Nostalgia in Post-Soviet Art and Literature. In: S. Dickinson, ed. Melancholic Identities, Toska and Reflective Nostalgia. Bologna: s.n.

Margalit, A., 2011. Nostalgia. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, I(21), pp. 271-280.

Maria Todorova, Z. G., 2012. Post-Communist Nostalgia. 1st ed. New York: Berghahn Books.

Massimiliano, G. & Jarrett, G., 2011. Ostalgia. [Art] (New Museum).

McCrystal, R., 2017. The Commissar Vanishes: The falsification of images in Stalin’s Russia. News and Features, Volume 46.02.

MoMA, 2012-2013. Faking It. [Art] (MoMA).

Pancheva-Kirkova, N., 2013. Between Propaganda and Cultural Diplomacy Nostalgia Towards Socialist Realism in Post-Communist Bulgaria. [Online]

Available at: https://www.scribd.com/document/220436391/Nina-Pancheva-Kirkova-Between-Propaganda-and-Cultural-Diplomacy-Nostalgia-Towards-Socialist-Realism-in-Post-Communist-Bulgaria?doc_id=220436391&order=616623204

[Accessed 6 November 2023].

Pančić, T., 2013. Yugonostalgia and Yugoslav Cultural Memory. Lexicon of Yu Mythology, Volume 72, pp. 54-78.

Pivovarov, V., 2015. The Angent in Love. s.l.:Garage Museum.

Shaw, C. & Chase, M., 1989. The Dimentions of Nostalgia.. In: The Imagined Past – History and Nostalgia.. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 2-10.

Stilyagi. 2008. [Film] Directed by Valery Todorovsky. Russia: Russia-1.

Štroblová, K., 2020. Whose Nostalgia is Ostalgia?Post – Communist Nostalgia in Central-European Contemporary Art, Ostrava, Czech Republic: BIBLIOTEKARZ PODLASKI.

Tate, 2012. Five Things to Know: Ilya and Emilia Kabakov. [Online]

Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/lists/five-things-know-ilya-and-emilia-kabakov

[Accessed 5 1 2024].

Tate, 2015. Meditation by the Window. [Online]

[Accessed 1 12 2023].

Taylor, J., 2019. Roentgenizdat (USSR), s.l.: Department of Music, University of Bristol.

Velikonja, M., 2009. Lost in Transition: Nostalgia for Socialism in Post-Socialist Countries. East European Politics and Societies and Cultures, Issue 23, pp. 535-551.

Wallach, A., 1991. Censorship in the Soviet Bloc. Art Journal, |(3), pp. 80-83.

Žižek, S., 2008. In Defense of Lost Causes. 1st ed. s.l.:Verso Books.