Sauda Mabuye 2024

Exploring Racism Within Design

5847 words | 32mins

Exploring racism within the design field for black designers between the 20th and 21st century

Introduction

Black graphic designers face certain obstacles and challenges that their white counterparts in the industry will not experience. These challenges can range from subtle biases to outright discrimination; for example, out of the “9,429 designers who filled out AIGA’s 2019 Design Survey, 71% of respondents were white, an overrepresentation in a country that’s only 60.4% white” (Eliza. M, 2020). The lack of representation and opportunities for black graphic designers in the design field has been a long-standing issue. Unfortunately, it is not a new one.

Throughout history, black graphic designers have faced significant barriers in terms of recognition, representation, and exposure. This lack of exposure means black graphic designers are not given the same opportunities to highlight their work and gain critical recognition. Another challenge that black designers may face is bias and discrimination in the hiring process. This can take the form of unconscious biases held by hiring managers, or more overt discrimination based on race. Additionally, the design world has been dominated by white voices, which has led to a lack of diversity in styles, perspectives, and themes.

This exclusion of black graphic designers is a cause for concern, and has been prevalent for far too long, as it limits the diversity of perspectives and experiences that can be brought to the table. Despite the countless contributions of black graphic designers to the industry, their presence in the profession remains minimal. This raises the question of why the design field has not made better use of the talents of these individuals. One potential reason for this underrepresentation could be the lack of access to educational opportunities in the field. Design education can be expensive, and students from marginalised and racialised communities may not have the financial means to pursue this career path. Additionally, the lack of diversity in the design industry can create a cycle of exclusion, where black graphic designers struggle to enter the field due to the limited opportunities available.

Professional training and education for minority designers have identified cultural bias as a significant obstacle preventing qualified black people from entering the design field. Holmes (1987) stated in her article Black Designers: Missing in Action that “the obstacle preventing qualified blacks from entering the design field is cultural bias.” The bias can manifest in various ways, including the underrepresentation of black graphic designers in the industry and the lack of diversity in design teams.

The issue of ‘Tokenism’ remains a persistent issue in the graphic design industry for black graphic designers. Tokenism refers to the practice of including a person from an underrepresented group to give the appearance of diversity. In What is Tokenism, and Why Does It Matter in the Workplace? (2018) Kara Sherrer explains the notion by explaining it as “the practice of doing something (such as hiring a person who belongs to a marginalised group) only to prevent criticism and give the appearance that people are being treated fairly.” Many Black designers have experienced ‘Tokenism’ in the design industry, where they are often the only black person in the room and are expected to represent the entire Black community. This relates to Dorothy Hayes’ experience in ‘The Black Experience in Graphic Design: 1968 and 2020’ where she states: “My employment was simply a form of tokenism”

The graphic design industry, like many other industries, has been criticised for its lack of diversity and representation of Black professionals; as Lemara L. Prince (2016) writes: “Diversity in some cases, breeds tokenism.” While the lack of diversity within the design field certainly plays a role in this issue, it is also important to consider other factors that may contribute to the underrepresentation of Black professionals in graphic design. As C. D. Holmes (1987) writes: “the average black parent is not aware of “art” as being a field in which one can make a living.” In this case, the aesthetic influence that black African Americans have on contemporary graphic design can be seen as an overlooked topic that deserves more attention. Unfortunately, the lack of diversity in the graphic design industry has historically excluded black professionals and their unique perspectives from the field. The issue of diversity and inclusion is present in every profession, and the field of design is no exception. Black design professionals often feel like they do not belong in the industry, leading to a lack of confidence in their work. Additionally, a lack of exposure to prevailing aesthetic traditions can lead to a compulsive effort to feel accepted and successful which in turn hinders their ability to innovate. This links to Sylvia Harris’ (2022) argument in “Searching for a Black Aesthetic in American Graphic Design”, where she identifies the phenomenon of assimilating into mainstream aesthetic traditions as means of gaining acceptance and achieving success.

The History of Black Graphic Design Aesthetic

The design field is dominated by a Eurocentric tradition and perspective. This dynamic has placed black graphic designers at a systemic disadvantage, often denying them equitable opportunities.

One of the main reasons for this disadvantage is the lack of representation of black graphic designers in the existing design traditions. Many design traditions taught in design schools and used in the industry have been developed in Europe and do not reflect the African American experience. This lack of representation has resulted in a situation where black graphic designers are often forced to work within a framework that does not fully understand or appreciate their cultural background. The goal of design work is to create visually compelling and effective communication. However, for black graphic designers, the pressure to conform to mainstream aesthetics often makes it difficult for them to produce designs that are truly unique and reflective of their personal experiences. Additionally, it can make it harder for them to gain recognition for their work, as their designs may not fit neatly into existing design categories. The constant exposure to certain images, colours, textures, and other cultural stimuli shapes our understanding of what is considered attractive and acceptable. This lack of interest can have a long-term consequence for black students in the future life. The design industry has long been dominated by European aesthetics and standards, leaving little room for representation of other cultures and styles. As Jen Wang writes in Now You See it, Helvetica, Modernism, and the Status Quo of Design (2016), “Graphic design makes visual that paradoxical nature of white representation.”

According to Sales (2021) research in “ Extra Bold in Teaching Black designers,’ many young black designers have come to understand how the industry works and found ways to incorporate their appreciation for European design while still highlighting black and urban design in their choices. These designers have recognised the importance of diversity and representation in the design industry, and they are making strides to ensure that black and urban aesthetics are given the recognition and attention they deserve. By incorporating these styles into their brand choices, they are not only promoting diversity but also creating unique and innovative designs that stand out in a crowded marketplace. The issue of black designers assimilating into white culture is complex and multifaceted. Some believe that assimilation is a way for Black designers to succeed in a white society.

By adopting White cultural norms and values, black people may be better able to navigate social, economic, and political systems that are designed to advantage White people. However, assimilation can also be seen as a form of cultural erasure, where Black people are forced to abandon their cultural heritage to fit into a White-dominated society. Furthermore, assimilation often requires Black people to conform to White standards of beauty, behaviour, and language. This can lead to feelings of inadequacy, self-hatred, and a loss of cultural identity. The concept of Whiteness in design has been a topic of discussion for quite some time now. It refers to the tendency to incorporate Eurocentric principles and aesthetics in design, often resulting in the erasure of cultural identities and the promotion of a dominant, mainstream perspective. Kaleena Sales (2021, p.27) stated that “getting closer to Whiteness in our design can be met with feelings of accomplishment, as graphic designers” which indicates that some graphic designers may feel a sense of accomplishment when they successfully achieve this Whiteness in their designs, as it is often taught in design schools to cater to a broader audience. While it is true that designing for a mainstream audience is essential in many cases, it is important to recognize the impact of such design choices on marginalised communities. By erasing cultural identities and promoting a dominant perspective, it is risking perpetuating harmful stereotypes and excluding those who do not fit the mainstream mold.

The rich cultural traditions of African descent have been overlooked and suppressed by European influences. Sylvia Harris (2022, p.29) stated “black design vocabulary are found in the work of white designers”. The issue of cultural appropriation in design has been a controversial topic in recent years. It has been discovered that black design traditions have been inspired by black culture and have taken advantage of the market for black expressive style. However, this has led to questions about the appropriateness of black culture in design without showing appreciation or inclusivity for black designers in the industry. The problem lies in the fact that white designers often borrow from black culture without giving credit to the origins of the designs. This erases the cultural significance of the designs and perpetuates the marginalisation of black graphic designers in the industry. Instead of just appropriating black designs, white graphic designers should try to learn about the cultural significance of the designs and incorporate them respectfully and inclusively. Constructing and documenting a black design tradition is a crucial step towards recognising the contributions of African Americans in the field of design. While there already exists a small body of research on the lives of America's first black graphic designers, it is important to go beyond just chronicling their work. Many pioneering black designers focused on surviving hostile profession, prioritising Western standard design to gain acceptance in the mainstream. Consequently, their work often lacked personal and cultural expression reflective of their African American identity.

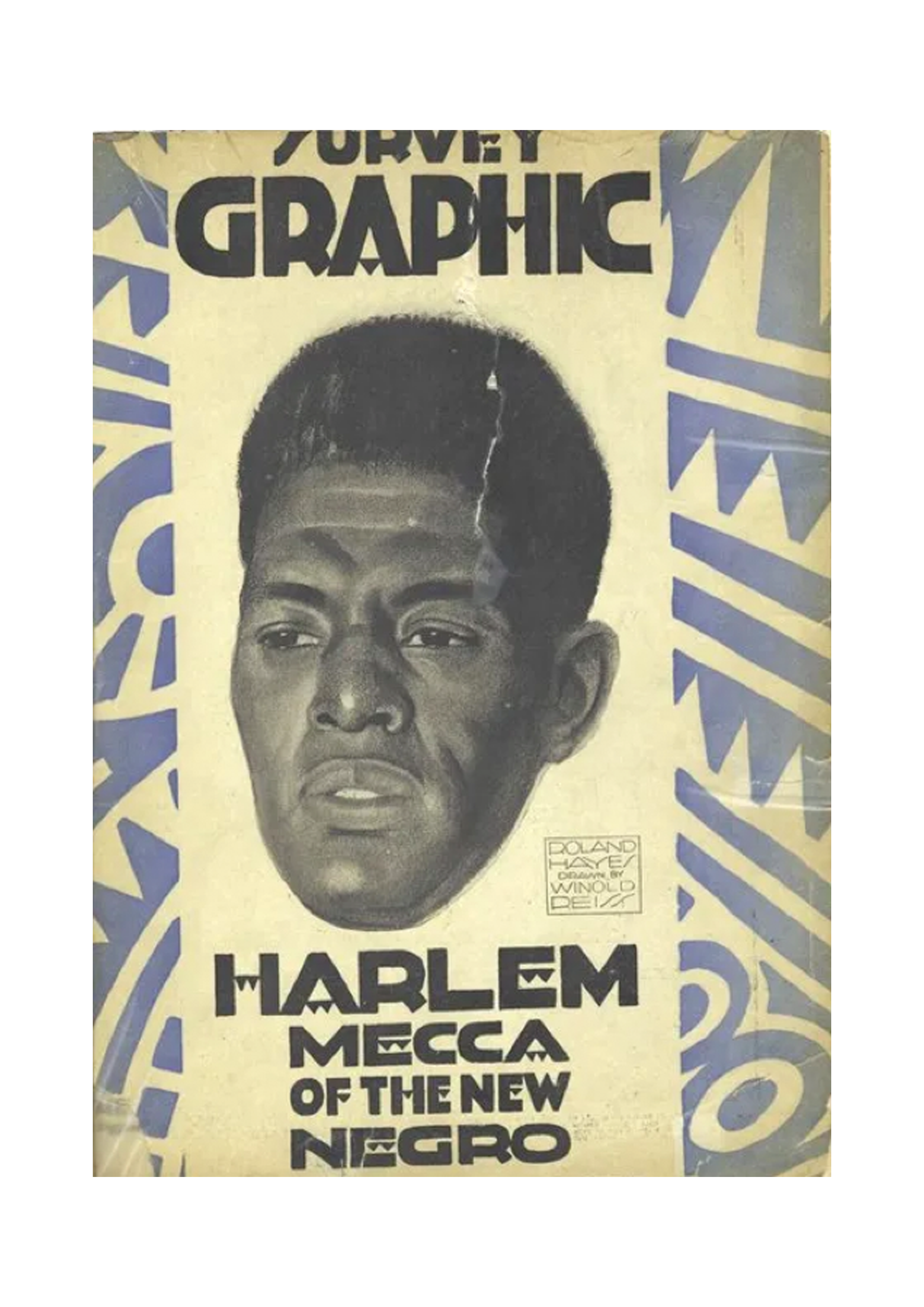

The "Harlem Renaissance" was a period of cultural and artistic revival among African Americans in the 1920s and 1930s. During this time, Alain Locke played a significant role in promoting the emergence of a "New Negro movement" and encouraging African American artists to draw inspiration from their own cultural heritage. Locke believed that black culture was a rich and valuable source of inspiration and content for African American artists, and that by embracing their heritage, they could create a new and unique form of art that reflected their experiences and perspectives. Locke's ideas were influential in shaping the artistic and cultural landscape of the Harlem Renaissance (1925). Alain Locke argues “the art of black people was a powerful inspiration to successful white artists, so why shouldn't black artists also work with this powerful force.”

Fig 1 - Harlem, Mecca of the New Negro (Reiss, 1925)

From the Harlem Renaissance to contemporary art, black artist has consistently been at the forefront of innovation and creativity. However, the question of why black artist should also navigate and conform to mainstream standards to engage with this influential cultural sphere. For too long, black art has been undervalued and overlooked in the mainstream art world. By embracing the power and influence of black art, black artists can not only create compelling and meaningful work but also challenge the status quo and push for greater representation and recognition in the art world. The 1920s was a period of cultural and artistic revolution. It was a time when the world was changing, and art was no exception. His advocacy for a "New Negro movement" helped to inspire a generation of African American artists, writers, and intellectuals to explore their cultural heritage and express themselves through their art. Through their work, these artists helped to challenge prevailing stereotypes and prejudices, and to create a new and positive image of African American culture that continues to inspire and influence artists today.

Harlem Renaissance, Sauda Mabuye (2023)

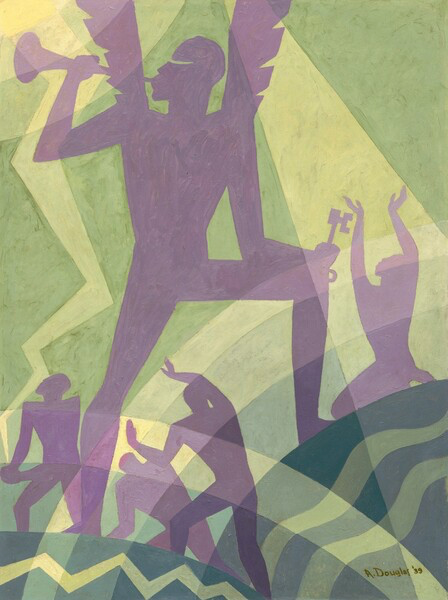

Black-owned journals were the best examples of this African aesthetic in the designs of the 1920s. The designers of these publications were often black artists who were influenced by European cubist painters, who, in turn, were influenced by African art. The African aesthetic was characterized by bold geometric shapes and vivid colours that were inspired by the art of African cultures. One of the best artists/designers of this era was Aaron Douglas, one of the pioneers of the African aesthetic who learned to recognise and resonate with the African in cubism. His designs were characterized by bold geometric shapes, strong horizontal and vertical lines, and vibrant colours. Douglas' work was widely recognized for its unique style and successfully captured the essence of the African aesthetic.

Fig 2 - The Judgement Day, (Douglas,1939)

The Black Art Movements by Larry Neal (1968) was a prominent figure in the Black Arts Movement, which emerged in the late 1960s. In 1968, he declared that he started the movement with the aim of an artistic and cultural movement that was firmly rooted in the African American community. Neal perceived the Black Arts Movement as a catalyst for challenging and transforming the prevailing cultural narratives that have historically marginalised Black artist. For Neal, the Black Arts Movement was not just about creating art that reflected the Black experience, but also about empowering Black artists and creating a new sense of cultural identity. He believed in the “aesthetic and spiritual sister of the Black Power concept” and saw it to promote Black pride, self-determination, and political activism. Under Neal’s leadership, the Black Arts Movement produced a wealth of literature, music, theatre, and visual art that celebrated Black culture and History while also challenging social and political injustices. The movement inspired a generation of artists and writers, and its influence can still be felt today in contemporary Black art and culture. The black arts movement and the black power movement were both important movements in the history of African American identity. Both movements were motivated by a desire for “self-determination and nationhood,” rooted in a deep sense of African American pride and identity.

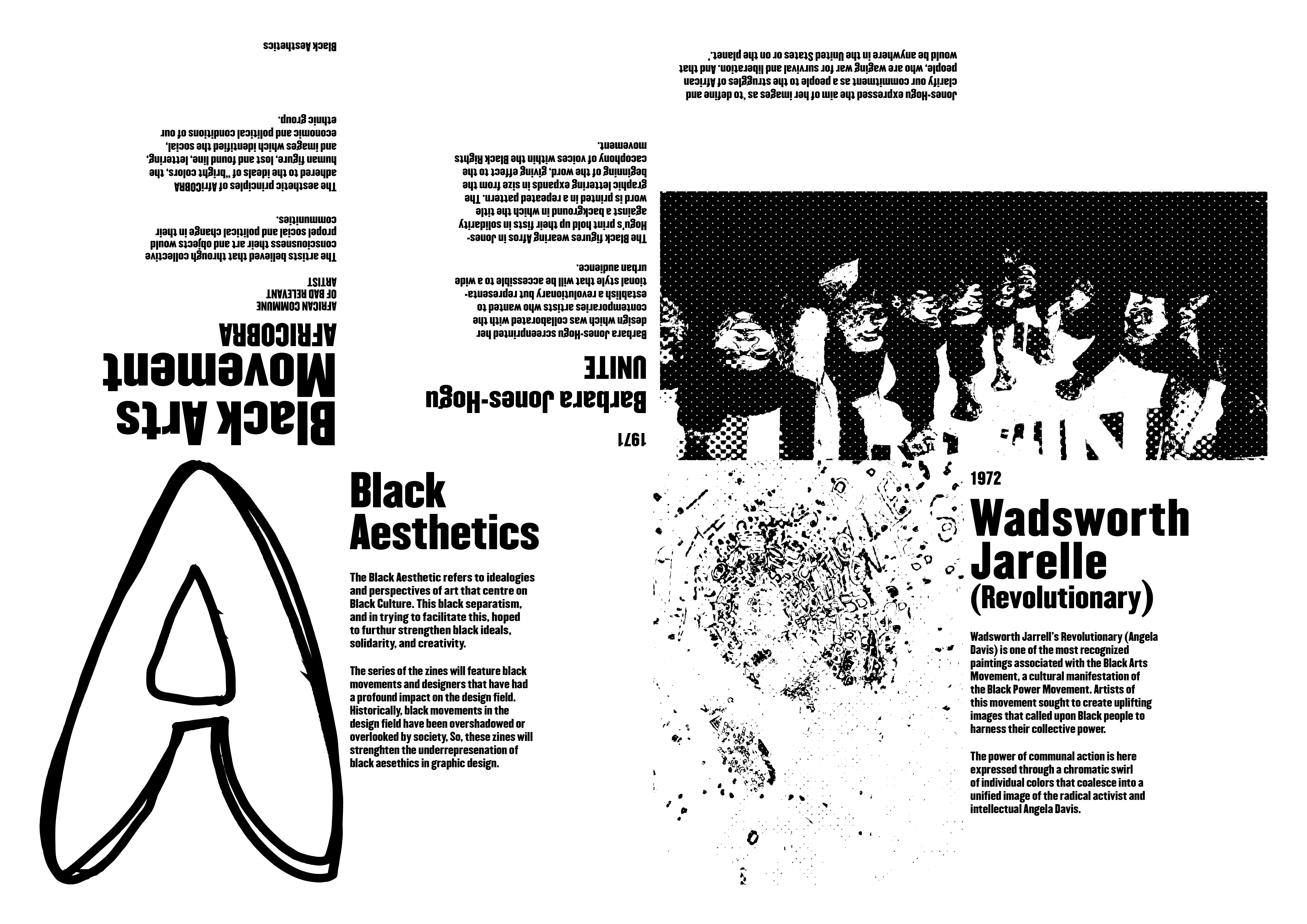

AFRI Cobra (The African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists) is a visual art collective founded in Chicago in 1968. The group emerged as part of the Black Arts Movement, which sought to create art that reflected the experiences and cultural heritage of black people, in contrast to the dominant Eurocentric artistic tradition. AFRI Cobra artists sought to create a new visual language that would capture the vitality and power of African and African American culture. AFRI Cobra’s art is characterised by bold colours, strong lines, and graphic shapes. The group’s work often incorporates images and symbols from African and African American culture, such as the Ankh, the African continent, and the Black Power fist. The artists of AFRI Cobra sought to create art that was both aesthetically powerful and politically relevant. They saw their work as a form of activism, using art to promote black pride and empowerment.

Fig 3 - Take it (Williams, 1971)

Black Aesthetics is a cultural ideology that emerged during the civil rights movement of the 1960s in America. It was a movement that aimed to promote and celebrate black culture, identity, and creativity. The black aesthetic encouraged black artists to create art that was reflective of their unique experiences and perspectives and use their platforms to address issues of social and political importance. One of the defining features of the black aesthetic was its promotion of black separatism in the arts. This meant that black artists were encouraged to create their unique forms of art, separate from mainstream white culture. It also meant that black art should be created by and for black audiences, rather than being created to appeal to white audiences. The aesthetic movements have an even greater impact on black graphic designers in America. Mo Woods (2020) states, “Expressions of racial pride encouraged Blacks through their art as a means for discovering and developing a system of African identity in America” During a time of intense racial discrimination and oppression, the aesthetic movement provided a source of inspiration and a platform for black designers to express their creativity and voice. By incorporating elements of African art and design, these designers were able to challenge the Eurocentric norms and create a unique visual language that reflected their own cultural identity.

Black Arts Movement, AFRI Cobra, Sauda Mabuye (2023)

Black design in contemporary times

The Harlem Renaissance lives on in the work of many black graphic designers who will continue to draw inspiration from its ornamental and expressive style. While the movement faced criticism for its focus on beauty over function, its impact on the design world and the ability of black graphic designers to find their voice cannot be overlooked. Furthermore, The Black Art Movement heightened the Black Aesthetic, which is a set of values and principles that define what is beautiful and meaningful in African American art. The Black Arts Movement, Black Power, and AFRI-Cobra Movement were all communities that played a significant role in defining the Black Aesthetic and “collectively embraced the notion that the Black aesthetic be rooted within the core of Black life” (Woods, 2020). These movements provided a platform for African American artists to showcase their work and connect with other artists who shared their cultural and political beliefs.

Through these communities, African American artists were able to create a collective identity and voice their concerns about social injustice and inequality. Graphic design has been a powerful tool in shaping the cultural and social narratives surrounding Blackness. Using visual elements such as colour, typography, and imagery, designers have been able to create powerful connotations of Blackness that challenge negative stereotypes and highlight the beauty, creativity, militancy, and pride of Black individuals and communities. “Graphic design was used to produce connotations of Blackness–Black as beautiful, creative, militant, and proud.” (Woods, 2020)

The graphic design industry is highly competitive, encompassing clients and practitioners. This field is known for being selective in its choice of participants, resulting in an evident graphic designer. Cheryl D. Miller explained: “there have always been many systemic barriers preventing marginalised communities in the U.S. from entering into the inaccessible field of graphic design.” Black graphic designers have a long history of facing significant challenges in their profession. Despite their immense talent and creativity, Black designers have been subjected to numerous barriers that have limited their opportunities for success. Systemic racism, also known as institutional or structural racism, refers to how racial groups are suppressed and discriminate against systems that are built to benefit certain groups over others. Consequently, systemic racism will affect black graphic designers who come to an understanding that “systemic issues means no longer viewing racist behaviors as isolated events and instead acknowledging the connections and historical underpinnings that contribute to the problem.” (Sales, 2021)

Graphic design education has revolved around white art movements such as the Bauhaus, Constructivism, and the International Typographic style, which have been widely celebrated as being the epitome of superior design. However, this has led to the exclusion of other design disciplines from many parts of the world, which has perpetuated the notion that white design is the only good design, “only one perspective then dominates the discourse on what constitutes valid design and who creates it.” (J. Wang, 2016)

It is often considered a fact that college admissions or entrants judge a student's work without knowing their ethnicity or gender. However, there are instances where entrants can identify a student's ethnicity based on their design aesthetic. As Pryce (2024) writes: “If you have people choosing those students and then they are not like those students, it is natural there you are going to infiltrate with what they are familiar with”. For example, a black student's perspective in style is influenced by their culture and experiences. This often results in expressive and bold designs that incorporate texture, layers, and vibrant colours. This aesthetic will affect them in the future life because it doesn’t abide by the European standard of design. As J. Wang (2016) writes, a “visual language that can exclude and invalidate the perspectives of non-whites…” is stopping the chances for black designers to not excel in conventions or competitions because they’re more willing to choose their traditional ways of design. This shows how the design field is not willing to embrace cultural diversity in the design field.

Taking Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality has been influential in understanding how different forms of oppression intersect, and how this intersection can lead to compounded marginalisation for certain groups, particularly women of colour. However, she has also applied this concept to design spaces, where she has identified a tendency towards a Eurocentric aesthetic that excludes other global diasporic cultures. In her thesis, Crenshaw argues that this preference for a European aesthetic is not just a matter of personal taste but is rooted in a larger system of power and oppression. By insisting on a narrow definition of beauty and design, we are excluding other voices and perspectives and perpetuating a system of exclusion and marginalisation. On top of that, she described how aesthetics is a fundamental aspect of design. They refer to the visual appeal of a product or artwork and are often used to evaluate the quality of the design. While aesthetics is often thought of as a subjective judgment, it is possible to view it as an objective judgment separate from the designer’s presentation. For a black graphic designer, you’re not being discriminated against because you’re a person of colour, it is because “your portfolio expresses your blackness in a way that does not conform to the aesthetic ideal” (Crenshaw, K. 1989)

Unfortunately, many black graphic designers who work at companies are promised opportunities that never materialise. Instead, they are often used as tokens, with their presence being touted as evidence of the company’s exclusivity “their token presence in the profession takes on added import” (Holmes, 1987). This lack of opportunity can be frustrating and disheartening, and it can prevent black designers from fully exploring their creativity and potential in their field. This type of tokenism can be harmful, Sadler. R (2021) states “Tokenism isn’t just oppressive systemically- it’s directly harmful to individuals” as it places undue pressure on Black designers to represent an entire community, rather than allowing them to be individuals with their unique perspectives and ideas. It also ignores the fact that Black designers have a variety of experiences and backgrounds and should not be reduced to a single identity. It's a sad reality that even with all the qualifications and efforts put into one's career, rejection can still be a common occurrence. However, for black professionals, this experience can be compounded by the uncertainty of whether the rejection is due to their race. E. Niles (2023): “If I wasn’t a person of colour. They would’ve employed me.” This uncertainty can create an added layer of stress and anxiety, making it difficult to move forward in their career. E. Niles (2023): “It does chip away at you eventually”.

Cheryl D. Holmes-Miller (1987) sums up that “you may not be good enough, or that you are a woman, or that you are black.” The issue of underrepresentation of Black designers in the creative industry is a systemic problem that has persisted for far too long: “levels of discrimination against black job applicants haven’t changed since 1990” (2017). However, every time a Black designer lands a good creative job, it serves as a beacon of hope and inspiration for other aspiring Black designers. As Kelly Walters (2020) says: “presence and talent serves to open the field further for other Blacks.” This shows it is important that established Black designers who have made it in the industry are willing to share their experiences and knowledge with talented but uninformed Black youth, as well as Black designers who are on their way up. Unfortunately, this willingness to share is not always forthcoming, and this can hinder the progress of Black designers in the industry.

Black students in the US tend to be attracted to Black universities because they’re offering education at an affordable price however the lack of exposure to graphic design curricula in Black Universities (HBCUs) is a significant barrier for black students who are interested in pursuing a career in graphic design. This results in a limited number of black college graduates (USA) who have been exposed to the possibilities of a career in graphic design. The graphic design industry, like many other industries, has been criticized for its lack of diversity and representation of Black professionals. In “2021 AIGA Design POV reported that only 4.9 per cent of counted graphic designers are Black” (2023). While the lack of diversity within the design field certainly plays a role in this issue, it is also important to consider other factors that may contribute to the underrepresentation of Black professionals in graphic design.

As C. D. Holmes (1987) found, 60 per cent of the black parents questioned wanted their children to enter more traditional professions, while only 5 per cent of the parents said they would like their children to enter some artistic field. It’s been proven that doing an education will lead towards a safe mainstream profession.

This refers to Cheryl D. Holmes-Miller's theory on ‘Missing in actions’ on how the lack of awareness in the design field for black of parents could be the cause of why there is a low percentage of black designers in the design field. Many black students are academically inclined and interested in pursuing a career in art or design. Due to societal pressures and cultural expectations, many black parents may discourage their children from studying art as a career, instead encouraging them to pursue more ‘traditional’ professions. Eddie Niles (2023), a graphic designer, recalls a similar family's lack of understanding about his choice of profession. He states “Lack of emotional support. It also comes back to your background. My family was against me going into art and design.”

The future of Blackness in design

Historically, black designers have faced various obstacles when pursuing a career in the arts. One of the challenges was the perception that the arts were not a practical way to make a living. This belief was based on the idea that the arts were not lucrative and could not provide a stable income, making it an impractical career choice. Furthermore, there was a belief that the arts were not suitable for black people to pursue because it was seen as a predominantly white profession. Despite these challenges, many black designers have preserved and pursued careers in the arts. For instance, Archie Boston was a pioneer in the advertising industry, breaking barriers as a black man in a white field. As a graphic designer and co-founder of Boston & Boston, he impressed people with his authentic portrayals of navigating AD land, drawing from his own experiences as a person of colour. Through his work, he sought to challenge stereotypes and promote diversity and inclusion in advertising. Boston's legacy continues to inspire and empower people of colour in the industry, reminding us that representation matters and that everyone deserves a seat at the table.

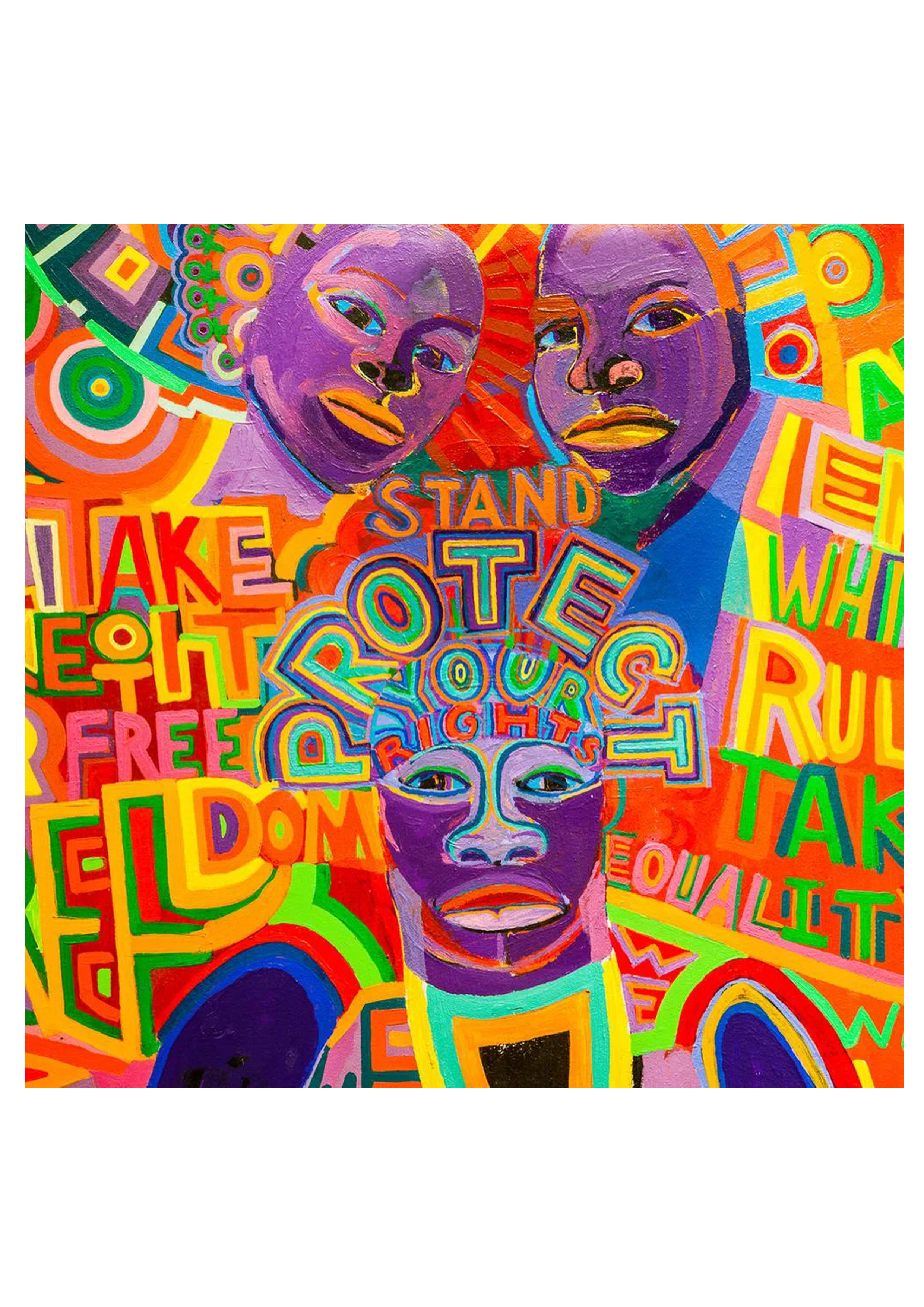

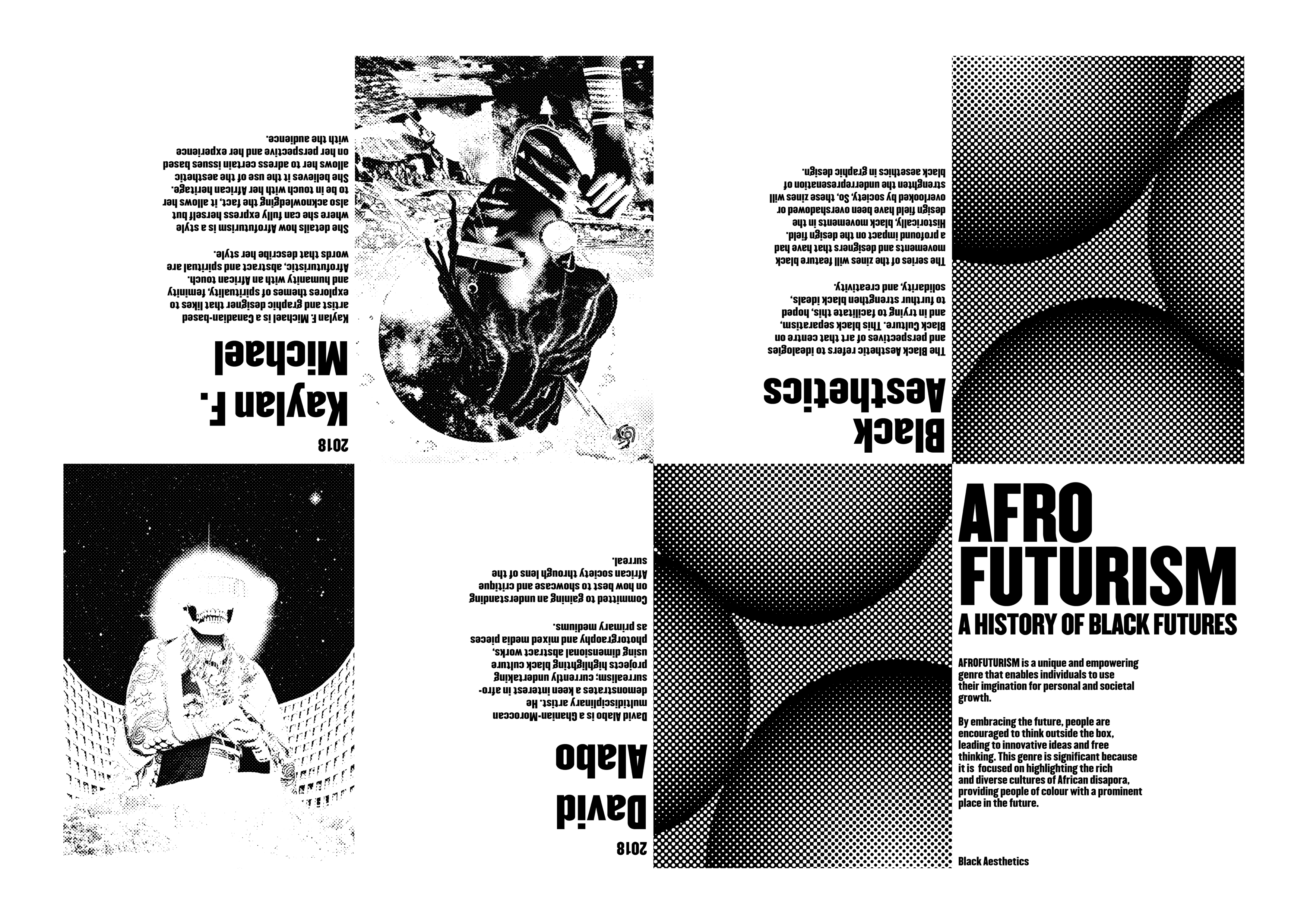

Afrofuturism is an artistic and cultural movement that combines elements of science fiction, fantasy, and African culture. At its core, is all about using the imagination to envision a better future for African people and the world at large. By drawing on both the past and future potential, Afrofuturists can create new narratives that challenge the status quo and inspire change. On the other hand, she details how “Afrofuturism encourages the beauties of African diasporic and gives people of colour a face in the future” (Y. L. Womack. 2013). It sets itself apart from past movements such as the Harlem Renaissance and the Black Arts movement. While those movements were focused on reclaiming and celebrating the historical past of the black community, Afrofuturism advocates for liberation from the limitations of the past and embraces a vision of the future that is inclusive of people of African descent.

AFROFUTURISM, Sauda Mabuye (2024)

It’s a response to the cultural hierarchies within design that have elevated European ideas and aesthetics above all others. By incorporating the perspectives and creativity of black minds, Afrofuturism aims to inspire new possibilities and solutions for the problems we face in our current society. It continues to recognise how the white-defined present and future have created systemic issues that disproportionately affect marginalized communities. By deconstructing these hierarchies and centring the voices of black people, Afrofuturism offers a way to imagine a future that is more inclusive and equitable.

The graphic design industry has the power to influence how people see the world, and it is important that this influence is inclusive and reflects the diversity of society. T. Huggins (2023) states “People of colour are getting a chance because companies must prove their diversity”. Diversity in the design field is crucial for innovation and creativity in all aspects of life and the design industry. “2-D diversity unlocks innovation by creating an environment where “outside the box” ideas are heard.”(How diversity Can Drive Innovation, 2013). When it comes to BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour) designers, diversity is especially crucial. It allows for a broader range of perspectives and experiences to be represented in the design process, leading to more creative and innovative solutions. One of the key benefits of having diverse designers is the ability to break down language barriers. For BIPOC designers who speak a different language or have a different background, navigating a design collaboration in Western culture can be challenging. Crenshaw’s thesis explains how the concept of cultural fit has become increasingly important in studio cultures, where collaboration is key.

As Crenshaws explains, there is pressure for individuals to fit into the culture of the studio, which is based on assumptions that having a shared language and culture will lead to better collaboration and better work. This is why cultural fit is often seen as an explicit element of studio culture. However, this emphasis on cultural fit can also lead to exclusivity and homogeneity within the design spaces. If individuals are expected to conform to a certain mould, there is less room for diverse perspectives and ideas. Crenshaw argues that studios should instead focus on creating a culture of inclusivity and respect for diverse backgrounds and experiences.

Now, today, institutions are collecting “students from a broad range of backgrounds and allow them to share their designs innovation in new and exciting ways” Cheryl D. Holmes (2016). By bringing together students from various parts of the world, institutions are creating a space for unique and exciting design innovation. These students can share their experiences, culture, and traditions, which can lead to new and groundbreaking designs that reflect a variety of perspectives. The inclusion of students from different backgrounds will improve the lack of diversity in the design field. “The design field itself is notably lacking in diversity of gender and ethnic representation” (Stone Soup Creative, 2020). The world of design has seen a significant change in recent decades with the emergence of black graphic designers bringing fresh perspectives and ideas to the industry. The term “people of term” encompasses individuals from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds who are not of European descent. Although the pace of change has been slower than expected, it is important to acknowledge the contributions of other people of colour who have broken through in the industry and provided unique content that strays away from the Eurocentric perspectives that are commonly seen in the field. As Cheryl D. Holmes writes: “Today, people of color make up more than 30% of RISD’s undergrad population” (2016).

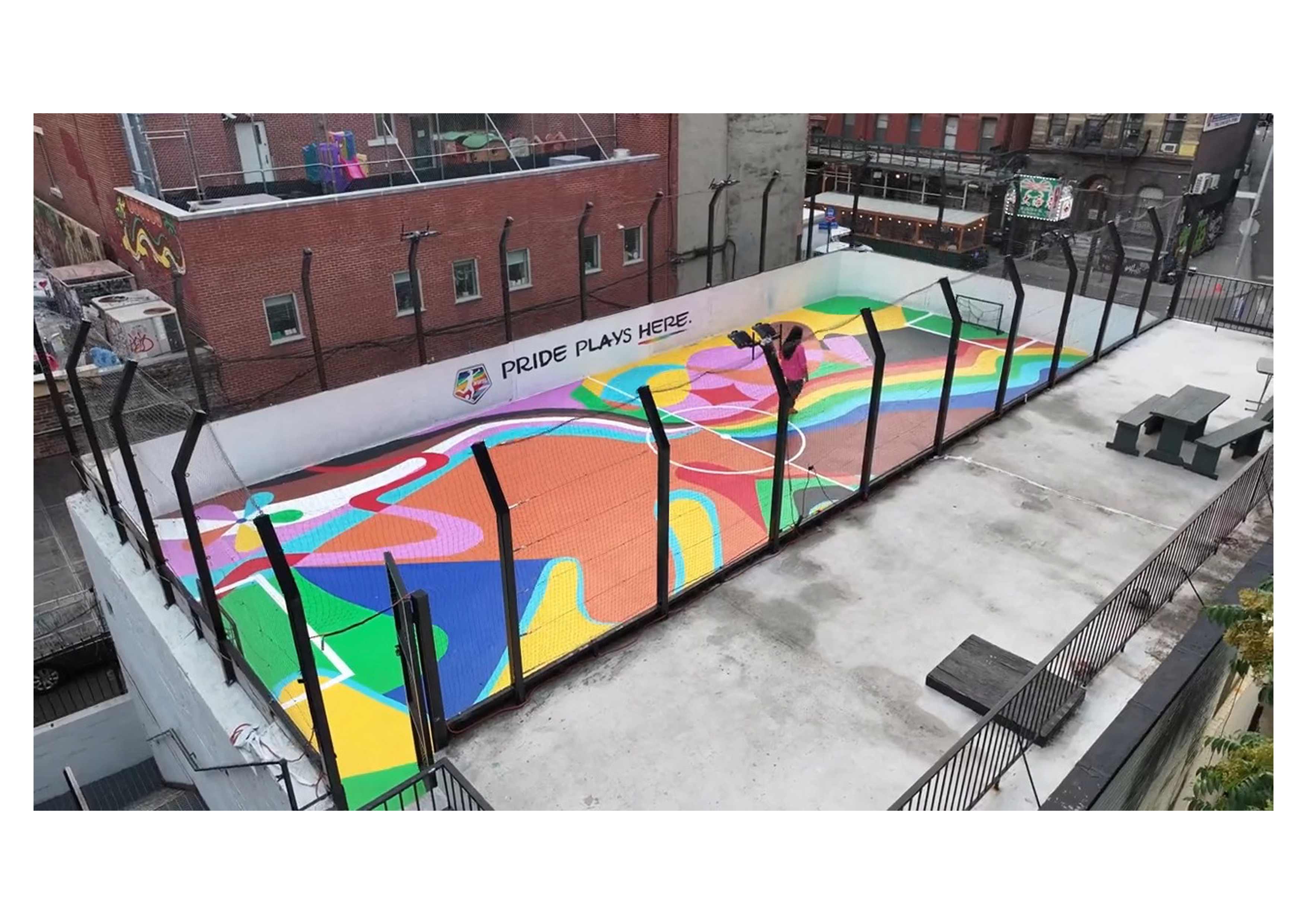

Black graphic designers have been particularly instrumental in bringing their cultural and personal backgrounds to their work, which has previously been overlooked or considered “different” from the norm. With their unique perspectives, black graphic designers have contributed to expanding the definition of design, making it more inclusive and reflective of the world we live in today. For example, Sophie Yeshi is an incredibly talented and passionate illustrator and graphic designer based in Brooklyn, NY. Her work is widely recognized for its vibrant colours, organic shapes, and joyful figures. Sophie is a queer Black and South Asian artist whose work aims to shine a light on Black women, women of colour and the LGBTQIA+ community. Sophie's work is not only aesthetically pleasing, but it also carries a deeper social and cultural significance. She uses her creative talents to create culturally relevant work that centres around topics she is passionate about, such as LGBTQIA+ pride, mental health awareness, and support for underrepresented business owners.

In Yeshi’s designs, she collaborated with NWSL to create a community “Pride Pitch” at the Ground NYC, a local soccer facility in Chinatown, featuring all 11 colours of the Rainbow Pride Flag. Her inspiration behind the “Pride Pitch” was the notion of pride being in the DNA, and not being able to be separated from a player's performance. The organic and overlapping shapes speak to the intersectionality and connectivity present in the game. For her, it was a privilege to create this design as a Queer artist.

Fig 4 - National Women’s Soccer League, Pride Pitch: The Ground NYC (2023)

Conclusion

It is important to acknowledge the challenges that black graphic designers face when working in a predominantly white design industry. These obstacles can include a lack of diversity in hiring, unequal opportunities for growth and promotion, and a general lack of understanding and appreciation for the unique perspective and experience that black graphic designers bring to the table. However, it is also important to recognise the potential for positive change in the industry. By actively seeking out and promoting diverse talent, providing equal opportunities for growth and development, and creating a culture of inclusivity and understanding, the design field has the potential to become a more welcoming and supportive space for all designers, regardless of race or background. It is up to all of us to work towards a more equitable and just industry and continue to push for progress and change, both within our work and across the wider design community. As a black art student, I must come to an understanding that I will face unique challenges as I navigate the design industry, but it is important to acknowledge and address how the design industry has historically excluded or marginalised individuals from underrepresented communities.

As a designer, I have the power to create work that is inclusive and representative of diverse perspectives. This can be achieved through conscious decision-making in your design process, such as choosing images or language that accurately reflect a variety of experiences and identities.

Bibliography:

Eliza Martin (2020) Design Diaries: Inside the Diversity Problem in the Design Industry, Ceros.com, Aug 20. Available at: https://www.ceros.com/inspire/originals/design-industry-diversity-problem/ (Accessed: 18 December 2023).

Anne, H. B (author), Kareem, C, Peninsula, A. L, Lesley-Ann. N, Jennifer, R and Kelly, W. (eds) (2022) The Black Experience in Design: Identity, Expression & Reflection. Introduction 0.2: Searching for a Black Aesthetic in American graphic design: Sylvia Harris. Pg. 28

Cheryl D. Holmes (1987) Black Designers: Missing in Action, printmag.com, June 27. Available at: https://www.printmag.com/design-culture/black-designers-missing-in-action-1987/

Kara. S (2018) ‘What is Tokenism, and Why Does it Matter in the workplace?’, business.vanderblit.edu, Feb 2018 (Accessed: 10 October 2023). Available at: https://business.vanderbilt.edu/news/2018/02/26/tokenism-in-the-workplace/

Ellen, L. Farah K. Jennifer. T, Josh, A. H, Kaleena, S. Lesile, X. and Valentina, V. (eds) (2021) (The Extra Bold: a feminist, inclusive, anti-racist, non-binary field guide for graphic designers, The Teaching Black designers by Kaleena Sales. Pg. 27

Lemara L. Prince (2016) “Diversity breeds tokenism, what we need is inclusion”: a post-election view on the US creative industry, It’s Nice That, Dec 2016 (Accessed: 18 December 2023). Available at: https://www.itsnicethat.com/news/us-creative-industry-privilege-lemara-lindsay-prince-191216

Anne, H. B (author), Kareem, C, Peninsula, A. L, Lesley-Ann. N, Jennifer, R and Kelly, W. (eds) (2022) The Black Experience in Design: Identity, Expression & Reflection.

Larry Neal (1968) The Black Arts Movement: Drama Review, Summer 1968 https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/maai3/community/text8/blackartsmovement.pdf (Accessed: 9 November 2023).

Dangerous Object (2016) Now You See it, Helvetica, Modernism, and the Status Quo of Design by Jen Weng, medium.com, Dec 2016 (Accessed: 21 December 2023). Available at: https://medium.com/@earth.terminal/now-you-see-it-110b77fd13db

The Black Aesthetic: Envisioning Blackness in American Graphic Design by Mo Woods (2020), medium.com, May 2020. Available at: https://medium.com/envisioning-blackness/the-black-aesthetic-envisioning-blackness-in-american-graphic-design-14de325d07b4 (Accessed: 28 December 2023).

Ellen, L. Farah K. Jennifer. T, Josh, A. H, Kaleena, S. Lesile, X. and Valentina, V. (eds) (2021) The Extra Bold: a feminist, inclusive, anti-racist, non-binary field guide for graphic designers, system racism by Kaleena Sales. Pg. 12

Pryce, S (2023) ‘Black Professional Practice’ by Sauda Mabuye (11 Dec)

Cheryl D. Holmes (2016) Volume 2: Still Missing in Action? printmag.com, Summer 2016. Available at: https://b960fbd8-b335-4bd0-8b73-f001c69ae98c.usrfiles.com/ugd/b960fb_d60d228a1c7249929ee7512b13688582.pdf

Anne, H. B (author), Kareem, C, Peninsula, A. L, Lesley-Ann. N, Jennifer, R. and Kelly, W. (eds) (2022) The Black Experience in Design: Identity, Expression & Reflection. Introduction 0.4: DESIGNING WITH COMPLEXITY: AN INTERSECTIONAL VIEW, Pg. 42-43

Black Graphic Design History: Influence and Impact (2015). Available at: https://www.adobe.com/express/learn/blog/black-graphic-design-history (Accessed: 30 December 2023).

Niles, E (2023) ‘Black Professional Practice’ by Sauda Mabuye (15 Dec)

Lincoln Quillian, Devah Pager, Arnfinn H. Midtoen, and Ole Hexel (2017) ‘Hiring Discrimination against Black Americans Hasn’t Declined in 25 Years’, hbr.com, Oct 2017. Available at https://hbr.org/2017/10/hiring-discrimination-against-black-americans-hasnt-declined-in-25-years (Accessed: 30 December 2023).

Huggins, T (2023) ‘Black Professional Practice’ by Sauda Mabuye (12 Dec)

Slyvia Ann Hewlett, Melinda Marshall, and Laura Sherbin (2013) How Diversity Can Drive Innovation, hbr.org, Dec 2013. Available at: https://hbr.org/2013/12/how-diversity-can-drive-innovation (Accessed: 5 January 2024).

Anne, H. B (author), Kareem, C, Peninsula, A. L, Lesley-Ann. N, Jennifer, R. and Kelly, W. (eds) (2022) The Black Experience in Design: Identity, Expression & Reflection. Introduction 0.4: DESIGNING WITH COMPLEXITY: AN INTERSECTIONAL VIEW, Pg. 41

Stone Soup Creative, Designing with An Awareness of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI), December 2020. Available at: https://www.stonesoupcreative.com/designing-with-an-awareness-of-diversity-equity-and-inclusion-dei/ (Accessed at: 5 January 2024).

Black Arts Movement, AFRI Cobra, Sauda Mabuye (2023)

Williams. G (1971) Take it. 127 x 127 x 6.4 cm (about 2.52 in)

Stevens. N (1970) Jihad Nation. 1080 x 1080 mm (about 3.54 ft)

Douglas, A (1939) Judgement Day. 121.92 x 91.44 cm

Harlem Renaissance, Sauda Mabuye (2023)

Rachel Sadler (2022) ‘How to Avoid to Tokenism at work’, shegeeksout.com, Apr 2022. Available at: https://www.shegeeksout.com/blog/how-to-avoid-tokenism-at-work/ (Accessed at: 14 January 2024)

Yeshi, S (2023) Pride Pitch: The Ground NYC. Available at: https://www.yeshidesigns.com/work/nwsl-pride (Accessed at: 14 January 2024)

Ytasha L. Womack (2013) Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture, c.12, p. 191