Introduction

To those who consider themselves right (handed),

“If you could sit in a dose of discomfort for a day, would you notice the smudged hands, the wrong swipes, the tapping in on the wrong side. Would you wonder why scissors hurt your knuckles as they fold the paper instead of a clean slice?

Would you be enlightened about our right-handed world, or would you think this essay is trivial?”

Sincerely,

Southpaws

It seems to me that 10% of the population are left-handed, while the other 90% don’t think about it. It’s not surprising left-handers think about ‘handedness’ more than their right-handed counterparts when it is something that is pointed out to them daily through the design of the world around them. Although we are not the only species to have hand dominance, cats, red kangaroos, and sulphur-crested cockatoos is to name a few are animals where being a ‘leftie’ is the nor. Luckily for them the natural world isn’t as biased towards left-handers as the world we’ve designed for humans.

Growing up left-handed I was lucky to live within a culture and time where ‘handedness’ didn’t matter. It’s never had much of a negative impact on my life, as I’ve adapted like many others to the annoyance of certain appliances and accepted my smudged handwriting. In fact, my ‘handedness’ hadn’t properly burdened me to the point of conscious thought, in a long time, until I had to do calligraphy workshops in the first year of university. It wasn’t until (after struggling) I heard mention of a left-handed calligraphy pen as an option, and it was only that it even occurred to me that I was disadvantaged due to being left-handed. Not only was I heavily rotating the page, a normal adaption to prevent smudging, but the pushing and pulling to create the letter formations due to the angled calligraphic pen was in the complete opposite direction to my peers and stood out to me after pages upon pages of repeated versions. It was great to be given the option of a left-handed pen, yet the accessibility of it compared to the right-handed pen (which was provided free of charge), let alone the price, wasn’t much to be excited about. So, I ended up, once again, adapting.

With a lack of accessibility and bias in design, every left-hander has had to adapt while growing up, to do things the ‘right’ way by completing tasks backwards. Although, it could be said this bias has been positive for left-handed people, forcing them to adapt to the right-handed world and even gain strengths that their right-handed counterparts don’t have. Multiple studies argue that it gives advantages in areas such as interactive sports (Faurie & Raymond, 2005). and perhaps can even be seen when comparing the writing of people’s non-dominant hand. Yet, whether this is universally true or not, it shouldn’t be the norm that left-handers must fit into the right-handed world, especially when it negatively impacts our lives.

The history of being left out

Figure 1: Cueva de las Manos, Gimenez (2012)

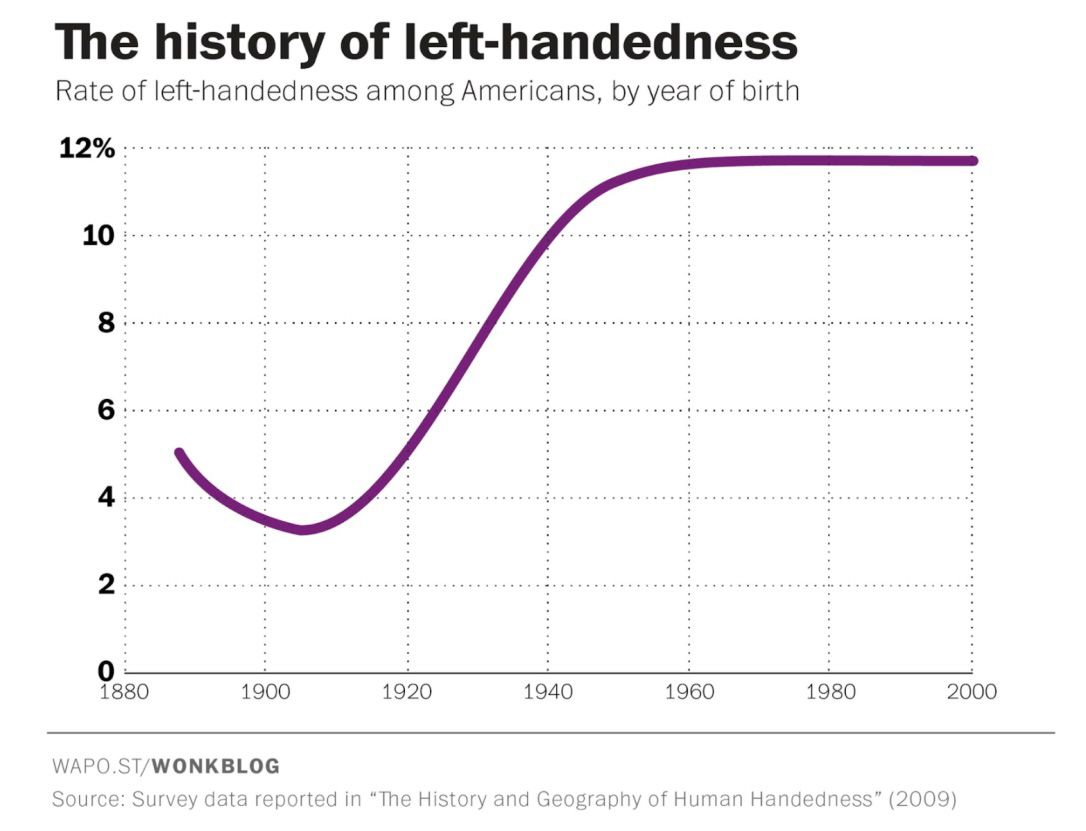

Figure 2: “The Surprising Geography of American Left-’handedness’”, Ingraham (2015)

Left-’handedness’ has existed at least since Neolithic times. With evidence dating back through Neolithic cave paintings and tools, even our distant ancestors showed hand dominance with a minority using their left one. Cueva de las Manos (fig. 1), a cave in in Santa Cruz, Argentina, contains over 2,000 handprints, likely stencilled using a bone spray pipe, with some prints dating back over 13,000 years. Interestingly, many of the hands on the cave walls are left, with a small proportion of right – suggesting that people held their tools with their dominant hand while placing the other on the wall. The mass of left hands and minority of right displayed reveals that left-handers have always made up a small percent of the population, and despite at least 13,000 years, it still continues that way. Examining ‘handedness’ through a historical perspective may help us understand the context of how it is viewed today. The History of Left-’handedness’ Graph (fig. 2) supposedly documents left-’handedness’ in America from the 1880s to present, and at first appearance seems to show the percentage of left-handers increasing over time. However, it then levels out. Therefore, one could argue it documents the stigma of left-’handedness’ changing over time, as when people weren’t persecuted for their ‘unusual’ hand dominance, more people felt comfortable to use their left hand. This ‘trend’ isn’t reserved to just left-handed people by any means. We could study similar graphs highlighting the same trends in relation to social acceptance, within the LGBTQIA population or other minority groups, which on a bigger scale stresses the importance of having a more accepting society and the de-stigmatisation of differences.

It is key to note that this graph is only reflective of one country and the cultures within it. Although a similar scale would also accurately document this trend for some Western countries, many countries in Asia still have lower levels of left-’handedness’ due to stigma and punishment for using your left hand. Countries such as the UK, USA, Canada, Switzerland and France average between 10 to 13% of their population being left-handed yet India, Taiwan, Japan, China and Korea all have lower than 5.2% left-handers (Ingraham, 2021), showing that their left-handers are still having to adapt due to the bias towards them.

Looking into the Etymology of the word itself, ‘left’ has various probable origins, the most common in the English language stemming from around 1200, when the old English ‘lyft’ meant ‘weak’ or ‘foolish’ (Online Etymology Dictionary, 2021). Pairing this with ‘right’ being a synonym for ‘correct’, it’s not surprising why people were judged for using their left, when it is literally engrained within the language. This isn’t just limited to the English Language however, with the French word for left ‘gauche’ having similar negative connotations including ‘clumsy’ (Merriam-Webster, no date). Furthermore, ‘dexterous’ a word used to describe being skilful with your hands, stems from the Latin ‘Dexter’ meaning ‘on the right side’ (Online Etymology Dictionary, 2022), and therefore carries the undertone of the right side being better than the left. This language bias isn’t restricted to left-handers by any means, with many words attributed to minorities historically having negative connotations, linking to a common theme of prejudice.

Delving further into the stigma behind left-’handedness’, and transcending language, we also find it in religion. Within Islam, it is an established principle that your right hand is of honour and nobility, therefore, traditionally tasks such as shaking hands, putting on clothes and eating all done with your right. Consequently, the left is widely considered the “dirty hand” (Khalifa Saleh Al Haroon, 2017) and tasks such as cleaning yourself, using the toilet and taking clothes off are reserved for the left. This tradition extends past Islam to many different cultures in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia, perhaps linking to the lower rates on left-’handedness’ in some of these countries, (Ingraham, 2021). Although this may seem an odd perspective, it stems historically from a lack of available sanitation and is logical from a hygiene point of view. In other religions the perspective isn’t as clear cut, with Christianity and Buddhism having numerous amounts of imagery and associations with the ‘right path’ where right represents strength and good. In Christianity, early paintings of the devil depicted him as left-handed, and “in the 17th Century it was believed that Satan would baptise his followers with his left hand” (Anything Left-Handed, no date), reinforcing this negative association. This devil connection also fed into the persecution of women as ‘witches’, as people believed they used their left hand to greet the Devil. Linking back to etymology surrounding left, the word Sinister derives from the Latin origin ‘Sinistra’, meaning left. With sin defined as “an offense against religious or moral law” (Merriam-Webster, no date), it furthers the idea that left-’handedness’ is evil.

Despite this, it’s worth noting there are a few examples of cultures that embraced left-’handedness’. The Ancient Celts supposedly worshipped the left side, associating it with femininity, a fertile womb and believing it was a force of life (Benningfield, 2019). Additionally, Tyr the Viking God of War, and the namesake for Tuesday was said to have had his right hand bitten off by a wolf making him left-handed. Described as having “courage and honesty, [using] his wisdom and power to stop wars instead of starting them” (Hidromiel Valhalla, 2019), he embodies a positive representation of left-’handedness’.

Figure 3: Thanos’ Infinity Gaunlet, Russo & Russo (2018)

Figure 4: Ned Flanders’ Leftorium, ‘When Flanders Failed’ (1991)

Despite this positive representation, unknowingly most media we consume is right-handed dominant, whether it be adverts, film or literature. Yet, when characters are purposefully left-handed it’s not uncommon for them to also be evil, furthering the religious and historical rhetoric that being left-handed is bad, which pushes a negative bias. This is seen back in the novel The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson (1886), whereby as Dr Jekyll transforms into Mr Hyde it is indicated he is writing with his left. More recent examples include Keyser Soze in The Usual Suspects (1995) and Thanos’ Infinity Gauntlet in Avengers: Infinity War (2018) - which is worn on his left hand while he uses it to wipe out half the universe (fig. 3). This then directly contrasts the next film Avengers: Endgame (2019), when the ‘good guys’ make a new Gauntlet to undo the damage, which happens to be right-handed.

Luckily one TV show has an overwhelming number of left-handers in it. Within the opening credits of The Simpsons (1990), Bart is in detention writing out lines on the chalkboard, with his left hand. Other characters in the animated show who are left include Mr. Burns, Ned Flanders and Marge to name a few, with Marge first shown as left-handed in 2010s episode ‘Boy Meets Curl’ (2010) where she reveals she only uses her right hand to avoid judgement. Albeit a throwaway line, it highlights how stigmatised being left-handed has been over time, and only how recently this has dissipated. Furthermore, Ned Flanders at one point owns ‘The Leftorium’ (fig. 4) an entire shop with tools specifically for left-handers (‘When Flanders Failed’, 1991). This large proportion of left-handers is all due to the fact that Matt Groening, one of the show’s creators is a Leftie himself.

Although there are examples of left-’handedness’ being embraced in the media, the feeling of bias in a world that is not designed for you can be viewed broadly in a feminist context through Caroline Criado Perez’s 2019 book Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men. Criado Perez (2019) explores the gender data gap and how it impacts women’s lives from the mundane of office temperatures not accounting for women’s bodies to how women are more at risk of injury in a car crash than men. Expanding on Simone de Beauvoir (1949), Criado Perez (2019) highlights how because men are seen as the default, women are ‘other’ and therefore not considered within in design. Many of the data gaps mentioned in the book boil down to designers as Criado Perez (2019) writes “They didn’t deliberately set out to exclude women. They just didn’t think about them. They didn’t think to consider if women’s needs might be different. And so, this data gap was a result of not involving women in planning_”_ (2019 p. 21).

This is the crux of the issue, ‘otherness’ being an afterthought, if even thought about, and highlights how the lack of awareness of a bias against left-handers within design means they are left out completely. One particular image study in the book (from 2017), discusses how technology reflects the bias is it fed, the more worrying fact being that sometimes this technology is significantly amplifies the bias it is taught, “pictures of cooking were over 33% more likely to involve women than men, but algorithms trained on this dataset connected pictures of kitchens with women 68% of the time.” (Criado Perez, 2021 p. 70) Through this we can see that an incorrect overrepresentation or underrepresentation will create a bias and can reinforce negative stereotypes; one which, if transferred to design, may impact people’s lives.

Another lens we can view this from is racial bias, and the ever-growing use of facial recognition technology. Since is it being employed at in increasing rate in all aspects of life, it is key that the technology is free from bias and accurate. Joy Buolamwini created the Gender Shade Project (2018), which examined and analysed the effectiveness of facial recognition software from Microsoft, Face++ and IBM. Boulamwini’s (2018) research highlighted that 93.6% of errors made from these software programmes were made when trying to identify an individual with darker skin. Researchers inferred, similar to Criado Perez (2019), that the systems were not given a range of faces diverse enough to mirror the global majority. The ramifications of this stretch far, as this technology is utilised for identification purposes. Furthermore, this isn’t the only piece of technology to display this racial bias, as automatic soap dispensers use infrared technology which shines light onto the skin and reflects it back to the dispenser. However, darker skin tones absorb light more than fairer skin, so reflects it back less. Consequently the dispensers have been shown as not working on darker skin tones (Pavey, 2017), highlighting the negative implications of being left out of a design decision. On an accessibility scale, left-’handedness’ is not for most people, a large prejudice that has a substantial negative impact on their life however, on a bigger scale it presents a data gap and design bias. The data gap for left-handers doesn’t have such heavy implications as racial design bias explored by Buolamwini (2018) and the gender bias explored by Criado Perez (2019), but they work in the same way through an absence of awareness.

Yet there are individuals who fall at an intersection of all these categories. Malina Moye, a “Trailblazing Left-Handed Black Female Guitarist” (Nepales, 2022), has talked about the biases she has faced as a female musician and African American woman in the music business. In an interview when asked about roadblocks in her career Moye states “being a guitar player and being Black, being a woman, being a left-handed guitar player who plays upside down… I already have three things... the higher up you go, you start to realize that a lot of women, and for me specifically, I say a lot of African American women haven’t been in certain spaces.” (Moye, 2023). This highlights further these biases through absence of awareness and need for accessibility.

Doing things the ‘right’ way

In Ancient Rome it was common courtesy to shake hands with your right. By extending the right-hand Romans showed they had no intention of harming the other person, as weapons were held in your dominant hand, so you were defenceless in a handshake. This was custom until Julius Caesar made it law to use your right to shake hands. Being a leftie himself, it meant he had the advantage of keeping his stronger weapon hand free to defend himself against potential disloyalty (Lefty’s, no date). So technically, doing things the ‘right’ way gave him an advantage, even if it was an unfair one. Living in a right-handed world full of right-handed design forces you to think differently to overcome hurdles when left-handed options are limited.

It has historically been common across the world to deter a child from writing with their left hand. In Victorian England specifically, the beginning of universal education meant children were taught to write with dip pens. For left-handers this led to smudging of work and facing social pressure to use their right along with physical punishment including tying the left hand behind a person’s back or caning (Chris McManus, 2007). It’s worth noting here, that ‘handedness’ is not a choice, yet the reason behind ‘handedness’ is still unknown. Although numerous hypothesises and papers debate whether genetics or environmental factors have a larger part to play, none have proved to be unequivocally certain. To summarise by quoting Psychologist, Michael Corballis (1997), there is “no agreement about how to define left-’handedness’”. There have been countless individuals over different periods of time who have been forced to use their right hand, due to the belief ‘handedness’ is a conscious choice. Despite this, many revert to their left-hand later in life, because it’s what is natural to them. I was able to talk to different students and learn first-hand about their culture’s viewpoints on ‘handedness’ in school. According to one of them, in China children are encouraged to use their right hand, as it fits in with their idea of a ‘perfect child’. Furthermore, a student from Portugal said she was born left-handed but forced to use her right hand in school, so is now more “ambidextrous”, highlighting that sometimes when left handers adapt its not out of their own choice but the social pressure and bias of their society.

Although pressures to adapt to the right-handed world typically stem from a biased view against the left hand, sometimes their outcome can benefit left-handers. There are numerous studies suggesting that left-handed people are more ambidextrous overall than right-handed people. This derives from the idea that lefties live in a world designed with right-handers in mind, so become adjusted to using their right-hand for certain tasks whereas right handers never have to do such things using their left-hand. This ranges from the everyday, including growing up using a mouse on a computer with your right hand, and fastenings on clothing, to using kitchen appliances and chainsaws. Although these tasks appear small, over time it aids the dexterity in your hand.

One of the studies proving this dexterity advantage conducted on 22 right-handed and 22 left-handed participants found that the left-handers “performed significantly better on the Purdue pegboard test when the task relied on the co‐ordination of both the left and right hands” (Judge & Sterling, 2017), which suggests an advantage in the non-preferred hand. We can also view left-handers’ strength in their opposite hand within sports, as they are an overrepresented percentage in many interactive sports. This in part due to a theory called the Negative Frequency Hypothesis (Faurie & Raymond, 2005). The hypothesis states that left-handed/footed players have an advantage compared to their right counterparts due to right dominant players having less experience with left-handed/footed opponents and therefore have a disadvantage in developing a tactical approach towards left-handed/footed opponents. This is shown by Hagemann (2009), who got left and right-handed tennis players at all levels (beginner, intermediate and expert) to complete a test where they were tasked with predicting the direction of an opponents’ stroke. The unanimous results across all groups showed the left-handed players were better at the prediction of right-hander strokes than vice versa. This supports Faurie & Raymond’s (2005) Negative Frequency Hypothesis, and partly answers why there is an overrepresentation of left-handers in interactive sports. These results emphasise further how left-handers’ adapt to a right-handed world and how in doing so can use it to their advantage. Even the term ‘Southpaw’ which is just another word for a left-hander, originally came from sports and was used as early as 1848 within boxing to describe a punch with the left hand (Klein, 2018).

In music many instruments require dexterity across both hands. It would be easy to assume from my earlier points that a left-hander would be more successful in these fields, due to living in this right-handed world, yet many instruments are also catered to the right. I played the piano as a child, and in talking to my parents about the topic of ‘handedness’ they recalled how they had a concern on whether learning the instrument would be harder for me as my left hand would have the bass line while my right hand would typically be carrying the ‘tougher’ melody. In a study published in 2011, researchers examined ‘handedness’ within musicians and whether left-handed pianists face a disadvantage. (Kopiez et al_.,_ 2011). The results from comparing 19 professional music students playing scales, concluded that there was no performance disadvantage for left-handed students. Interestingly, both right-handed and left-handed pianists had superior precision in the right hand, in comparison to the left. A key factor into studies such as this, is looking at the age the musicians started playing their instrument. The medium age of the participants in the study starting their instrument was 6.5 years old, showing this dexterity can be aided over years of practice. However, importantly, the study also noted that it’s not possible to rule out whether left-handed “instrumentalists subjectively feel constricted when playing in the standard position”, highlighting that despite adapting to the ‘right’ way of doing things, it could contribute to their personal discomfort (Kopiez et al_.,_ 2011).

Other instruments, such as those in the string section, require the hands to be doing completely different things. Typically, the left hand operates the fingerboard and the right hand to bow, pic or strum (Minnesota Orchestra, 2022). In cases such as the violin or cello the bow requires precision in the angle it is moved at, whereas with the guitar the left hand makes the chords while the right does the strumming of fingerpicking. It could be argued that this orientation of the guitar is beneficial to a left-handed player, as some find the chords more challenging, when strumming is easier in comparison. However, more complex guitar playing requires intricate fingerpicking with the right hand which tends to be more difficult than the left hand. To use any of these instruments left-handed is a challenge, since it’s not as simple as turning the instrument over due to the string order. With more traditional string instruments such as the violin, a left-handed version is hard to come by (Walker, 2020), perhaps due to the wider affect it can have on a professional musician, as playing left-handed can disrupt the order of orchestra seating. In relation to the guitar, overcoming this design bias in the 60s when left-handed models weren’t widely available was Paul McCartney, as he’d play upside down or restring a guitar, showing he was able to adapt them to work in his favour. Further proving that left-handers consistently overcome handed design bias (Jackie Kolgraf, 2023), linking back to Malina Moye,

Unfortunately, despite trying to adapt to the ‘right’ way as much as possible, there are certain professions of work where being left-handed can put you at a disadvantage. One study led by Prasad S. Adusumilli MD (2002), examined the medical field, looking at 68 surgeons in New York City. With a similar percentage of left-handed surgeons reflecting the population the study aimed to find out how their ‘handedness’ affected the training and career. Their research revealed that only 10% of surgeon programs mentored left-handed residents. Furthermore, only 13% of the programs provided instruments for left-handed surgical residents. Interestingly, even 10% of the left-handed surgeons from the study “expressed concerns when asked whether they would be comfortable being treated by another left-handed surgeon when they are the patients themselves” Prasad S. Adusumilli MD (2002), Which dramatically highlights the inconveniences of being a left-handed surgeon, to the point they feel like their training was lesser than their right-handed counterparts. Although this study was published two decades ago, recent reviews in 2010 and 2017 showed this was still a prevalent issue (Anderson, M. et al., 2017), (Tchantchaleishvili & Myers, 2010).

Another study that took place within the medical field focuses on dental students (Kaya & Orbak, 2004) since typically dental chairs are right sided, favouring right-handed practitioners. The study monitored two sets of students, one set included right and left-handed students using right-handed chairs to remove plaque, while the other group was solely left-handed dentists using left-handed chairs to complete the task. The results showed a significant difference in the outcome of left and right-handed students in the right-handed chair, with the right student excelling. Unsurprisingly the left-handed students worked better with the left-handed chair, 85.7% of them said they found the right-handed chair uncomfortable (Kaya & Orbak, 2004).

These examples highlight that even though medical professionals are adapting to a right-handed workplace, it is potentially to their patient’s detriment. Therefore, it’s not surprising to see that, according to a study from Joshua Goodman (2014), that left-handers earn around 10 to 12 percent less than right-handers. Other fields this also effects include manual labour with old school chainsaws designed for easier use for right-handers. Even when tools are viewed as ‘neutral’ most emergency controls are favoured to the right, so even if left-handers aren’t at a disadvantage using the machine, they are in more danger, assuming they are slower in operating these controls with their right hand. For woodworkers, 37% of all injuries in the field are hand injuries, but for those using saws hand injuries make up 67% of all injuries (Papadatou-Pastou, 2021). When using this machinery, a left-hander is “more likely to have an amputating injury of their dominant hand than were the right-handed (70% compared with 51%, respectively)” (Taras, Behrman & Degnan, 1995). All these workplace examples go to show, that although left-handers have adapted to a right-handed workplace due to the design bias in the tools they use, they are still at a disadvantage in comparison to their right-handed counterparts and that they would fare better with options designed specifically for them.

Design forces us to make (differently)

Despite most design clearly favouring right-handers, there are left-handed options out there. Just like Ned Flanders’ shop in the Simpsons (‘When Flanders Failed’, 1991), there are shops that solely cater to left-handed people and their needs; they just take some looking for. Many of these shops are online – meaning a wider range of people have access to them. With only around 10%-15% of the population being the target market, and a percentage of that demographic adapted to using tools the ‘right way’ it’s clear why so few of these shops exist in person, it’s just not that profitable. This reasoning likely accounts for the lack of left-handed products in mainstream shops, and the higher price point in left-handed products when featured in these shops, exacerbating this bias because of reduced accessibility. This is not a critique on left-handed products by any means, but more the accessibility of them for left-handers, specifically children.

We can evidently see from the Dental (Kaya & Orbak, 2004) and Surgeon (Prasad S. Adusumilli MD, 2002) studies, that by providing people with the right equipment suited to them, they are able to reach their higher potential. One study revealed “left-handed children perform worse than right-handed children in all areas of development with the exception of reading…. Quantitatively, the differences in development are important, with left-handed children scoring about 6% of a standard deviation lower in vocabulary tests, 7% lower in mathematics tests and 8% lower in comprehension tests than their right-handed siblings.” (Johnston et al., 2012) This clearly highlights the issues left-handers face from childhood, by being forced to fit into a right-handed world, and how it can have a vast impact. Yet the overwhelming lack of research focusing on left-’handedness’ and their needs highlight the absence of awareness of the need for left-handed design.

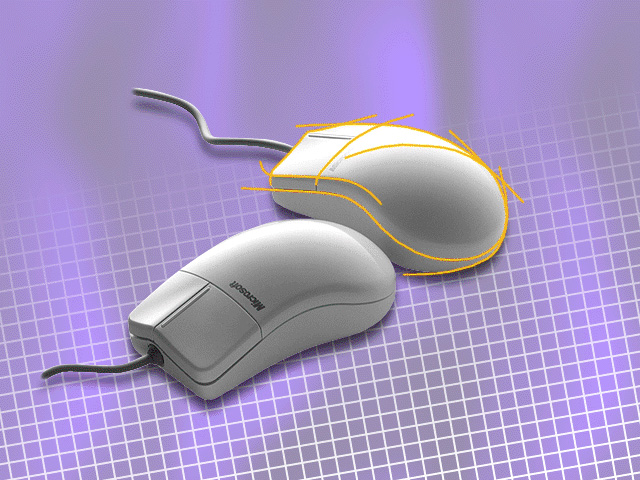

Figure 5: Microsoft Mouse 2.0 presentation, Taken from: https://guidebookgallery.org/

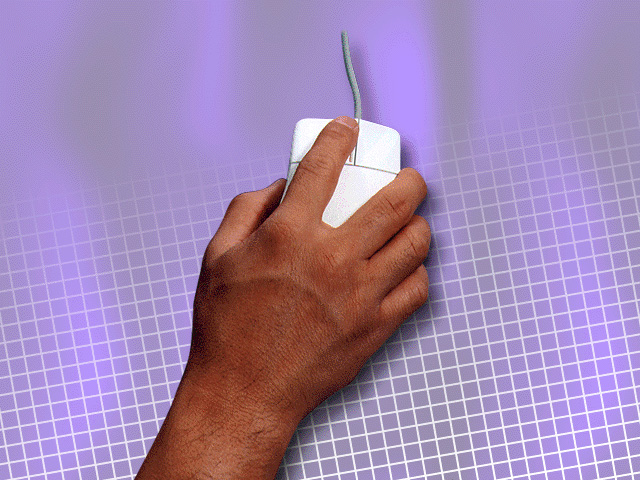

Figure 6: Microsoft Mouse 2.0 presentation, Taken from: https://guidebookgallery.org/

Sometimes design presents itself as neutral, and this isn’t limited to ‘handedness’ by any means. Typically stemming from data gaps which are in part from a lack of data collection but also partly from the bias of designers whose idea of neutrality is unintentionally (for the most part) exclusionary, as previously noted by Criado Perez (2019). A prime example of false neutrality within ‘handedness’ is the computer mouse. When first introduced, early commercial versions were symmetrical in design and though the buttons were programmed for the right hand this was reversible through software. Many ports on computers for mice were on the right side so by moving the mouse to the left side the cord was short and made it hard to use, something right-handed designers didn’t think of. In 1993 Microsoft reengineered the mouse when they brought out Microsoft Mouse 2.0 (fig. 5). This was a design claiming to be ergonomic for all; one that curved to the left in its kidney bean shaped and was clearly asymmetrical. Despite this, even in the presentation Microsoft created for the mouse, for its launch, it showed the mouse being used by a left hand (fig. 6). However, the hand shown is wearing a watch, something a left-hander wouldn’t do on their left-hand. It's not the only company to bring out these types of mouse designs, with some Trackball mice being similarly exclusionary, since the ball is placed to the left side of the mouse.

Examples of this bias go beyond computer mice, since even so-called ambidextrous scissors are not left-handed. The handles just look the same, so it can be flipped, and yet no matter if you flip it over the blades are still in the same position so it cuts the same way. Perhaps the issue lies with the marketing of these products, it is understandable to want a mouse or scissors that are easy to use but marketing them for both hands when they clearly favour the right is the problem. Some products have ‘handedness’ engrained in them, so when striving for an inclusive design, there will have to be more than one outcome. There will never be scissors or an ergonomic mouse that are truly ambidextrous, and that’s ok. What’s less ok is trying to present an item such as these as a one fits all or ‘neutral design’ towards ‘handedness’, when it physically can’t be. This presents another bias towards left-handers instead of a useful adaption. Therefore, the focus should be more onto reducing data gaps so design can be created with accessibility in mind and not neutrality. However, to even instigate a change, first these gaps need to be noted to understand where design is making those who fall outside of the design ‘norm’ invisible. To quote Kat Holmes author of ‘Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design’, “Designing for inclusion begins with recognizing exclusion_”_. In challenging this data gap, we are presented with the hope of creating design that is more inclusive, eliminating the design bias and the need to adapt.

In Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men, Criado Perez (2019), states that in most cases, until an inconvenience is noticed by a designer through a personal experience it won’t even be considered. She uses the example of Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg, who talks about her first pregnancy in her book Lean In: Women, Work and the Will to Lead (Scovell & Sandberg, 2013). Mentioning how, while working for Google, the company was massive and so was the car park, something that Sandberg only noticed when walking across it in her swollen pregnant state. After struggling for some time, she went to Sergey Brin, one of Google’s founders, announcing the need for pregnancy parking at the front of the building. He agreed, and they both noted how it was something they had never even considered before. This highlighted a data gap, one that shouldn’t have taken a senior member of staff to realise, as she wasn’t the first pregnant women in the office.

This links to research conducted by CV-Library, in a survey where 2,400 employees were asked about ‘handedness’, and it was revealed that 96.7% of UK employers don’t ask new staff if they are left-handed, while 25.4% don’t provide any left-handed office equipment at all, proving this data gap. This is an unsurprising omission since most employers are likely to be right-handed themselves and therefore unaware of the effect it could have on their employee’s work. Interestingly despite only around 12% of the UK population being left-handed 82.4% of those surveyed thought that it was their employer’s responsibility to provide equipment suitable for left-handers (Humm, 2015). A first-hand example of this happening was seen by my mum, a left-hander who works for an office furniture company and recently went to a supplier’s showroom to see their products. In discussing a new chair that had a desk attachment connected (akin to an American school desk) the supplier stated the attachment couldn’t be moved from the side it is fitted, therefore a left-hander would need a left-handed version of the chair. She voiced her concern on the desk attachment not being moveable to either side, stating many offices wouldn’t think about ‘handedness’, as shown by CV Library’s survey, so would only buy a few left-handed chairs, if any, without consulting their employees, therefore the item is unnecessarily exclusionary. This stumped the supplier and gives hope that if more people can think about accessibility, we have a greater chance in creating an increasing amount of accessible design.

There are already steps being put in place surrounding wider accessibility in design, in September 2018 the UK Government set out a regulation that required public sector bodies to include an accessibility statement on their websites, while also actively making the website or app more accessible for all (Central Digital and Data Office, 2018). By creating standardised accessibility information online and monitoring it by law, companies are held accountable for whether they are doing enough. Online, these features and tools can include alt text on images, the ability to change the text size and colour and to have the text read aloud. Additionally, there are books and online resources available to access that solely focus on educating people in designing for diverse needs. Practical examples of how inclusivity has been implemented in design to help eliminate and combat bias, include gendered AI.

When digital voice assistants were first introduced by Apple, first in the iPhone 4S, going by the name of Siri, and later by Amazon (in 2014), in the release of the Amazon Echo, with the name Alexa, there were a few commonalities that stood out, a key one being that both the assistants had female voices. With the aim of these devices being to carry out mundane domesticated duties it inherently reinforced subservient stereotypes of women and continued to negatively affect gender roles. It took Apple 3 years to release a male voice, but it took Amazon up until 2021 to introduce their male voice called Ziggy. The default remains with the female voice as the setting among most voice assistants, which is akin to computer mouses where the right click orientation is the default and you have to change the mouse orientation for a left-handed user. However, in early 2021 update Apple added more voices for customers to choose from and removed the default voice, by adding in the step of users manually choosing a Siri voice when initially setting up their device. In a statement included in the report by Apple they stated “These updates further Apple’s long-standing commitment to diversity and inclusion, with products and services that are designed to better reflect our customers and the world” (Apple_,_ 2021) Highlighting that by removing a default, one which isn’t neutral due to the negative stereotypes it carries, and by allowing users to have control, they can make more inclusive and accessible design.

A different approach to this kind of design can be seen in Q, the genderless voice AI that was launched in 2019. The voices used is unidentifiable as either male or female so breaks the binary of choosing between the two by creating a new category of neither (The Genderless Voice, 2019). This eliminates any negative biases that could be perpetuated by choosing a gendered voice for a voice assistant. These developments further suggest that if design can dismantle bias through elimination of biased options and creation of something other, perhaps other kinds of design, such as design orientated around ‘handedness’ can too, in such a way that no one has to adapt.

Conclusion: How not to be left out

Historically it’s not surprising and clear to see that the bias imposed on left-handers has forced them to adapt, from the extreme example of such bias toward right-’handedness’ putting left-handed people’s lives in danger, by being forced to use your right hand, to the contrastingly mundane issue of just trying to navigate a world full of right-handed designs. Even now the undertones and negative connotations of commonly used phrases such as ‘two left feet’ perpetuate the idea of left being worse than right, although not all of these adaptations are necessarily bad. As we’ve seen, lefties can use their ‘handedness’ to their advantage in sports (Faurie & Raymond, 2005) and have greater dexterity across both hands in comparison to their right-handed counterparts (Judge & Sterling, 2017). Yet, it’s hard to definitively categorise whether these forceful adaptations are wholly either positive or negative. Depending on the situation, I believe it can be either. While it seems almost trivial complaining about scissors being difficult to use as a left-hander, scaled up, it means Surgeons (Prasad S. Adusumilli MD, 2002) and Dentists (Kaya & Orbak, 2004) are worse off in their practice due to their ‘handedness’, and it’s clear that those are adaptations that shouldn’t need to happen.

The overwhelming takeaway from my research is that we need design to be more inclusive to everyone. Being in the left-handed minority from the perspective of ‘handedness’ is easier than many other groups who fall outside the centre of design. However, the best way to reduce these kinds of data and accessibility gaps is to have an accurate reflection of society present when designing, and to make people and designers more aware of the importance of accessibility. By enforcing accessibility rules, monitored by a governing body, it holds designers more accountable to these accessibility principles. While educating them on how they might be creating biased design unknowingly, it pushes design in a more welcoming direction. The promising part is that design seems to be heading in a more inclusive direction, with the introduction of accessibility guidelines and rules. By reading this, my hope is that the thought of ‘handedness’ stays with you, as a gateway into thoughts about larger aspects of accessibility, with the idea that if everyone more actively thinks about accessibility and making design that works for everyone, change will happen. So, in conclusion, hopefully Southpaws will soon be able to stop adapting to design, and that instead, it will adapt to them. Regardless, if I was given the option to be right-handed and forgo a life of smudged hands and minor inconveniences due to my ‘handedness’, I wouldn’t even consider it.

To those who consider themselves left (handed),

I hope you were never forced to use your right or get told you were wrong for using your left.

Yet if you could, would you change the annoyance of it all, the mass of minor inconveniences, the smudged hands, the backwards feeling. Or do you like the immediate bond you get from finding another left-hander, another one of the 10%.

I know I do.

Sincerely, A Southpaw

Bibliography

Introduction & Section 1

A sinister clue (no date) TV Tropes. Available at: https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/ASinisterClue (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Avengers: Endgame (2020). USA: Walt Disney studios home entertainment.

Avengers: Infinity War (2019). USA: Walt Disney studios home entertainment.

Beauvoir, S. de (2015) The Second sex. London: Vintage Classic.

Benningfield, B. (2019) A history of how the left hand became associated with evil and the devil, Ranker. Available at: https://www.ranker.com/list/left-hand-facts/bailey-benningfield (Accessed: 28 November 2023).

Buolamwini, J. (2018) Gender Shades Project, Gender Shades. Available at: http://gendershades.org/ (Accessed: 03 December 2023).

Criado-Perez, C. (2021) INVISIBLE WOMEN: Data bias in a world designed for men. New York: Abrams Press.

Dexterous (adj.) (no date) Etymology. Available at: https://www.etymonline.com/word/dexterous#etymonline_v_30233 (Accessed: 30 November 2023).

Gouache definition & meaning (no date) Merriam-Webster. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gouache (Accessed: 28 November 2023).

Groening, M. (1991) The Simpsons. United States: Fox.

Ingraham, C. (2021) Slow Reveal Graph. Available at: https://slowrevealgraphs.com/2021/11/08/rate-of-left-’handedness’-in-the-us-stigma-society/ (Accessed: 03 December 2023).

Khatri, S. (2017) #Qtip: Why Arabs don’t like to use their left hands, Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/dohanews/qtip-why-arabs-dont-like-to-use-their-left-hands-f690faa0bf4e (Accessed: 03 December 2023).

Kushner, H.I. (2017) On the other hand: Left hand, right brain, mental illness, and history. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lefty (no date) * history & culture, Leftys Left-Handed Products. Available at: https://www.leftys.com.au/index.php/fun-facts/history-culture (Accessed: 03 December 2023).

Left (adj.) (no date) Etymology. Available at: https://www.etymonline.com/word/left (Accessed: 30 November 2023).

McQuarrie, C. (1995) The usual suspects [DVD]. United States: Gramercy Pictures.

N/A (no date) ‘Cueva de las Manos’.

Papadatou-Pastou, M. et al. (2020) ‘Supplemental material for human ‘handedness’: A meta-analysis’, Psychological Bulletin [Preprint].

Schofield, K. (2023) Malina Moye brings her musicianship, message, and motivation to Krannert’s Ellnora Guitar Festival - IPM Newsroom, Illinois Newsroom. Available at: https://ipmnewsroom.org/malina-moye/ (Accessed: 09 June 2024).

Sin definition & meaning (2023) Merriam-Webster. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sin (Accessed: 28 November 2024).

Sinister and dexterity: Why ‘left’ is associated with evil (no date) Merriam-Webster. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/wordplay/sinister-left-dexter-right-history (Accessed: 28 November 2023).

Sinister definition & meaning (no date) Merriam-Webster. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sinister (Accessed: 30 November 2023).

Stevenson, R.L. (1997) The strange case of dr. jekyll and mr. Hyde. Colognola ai Colli (VR): Demetra.

The reason why the right hand is preferred over the left - islam question & answer (no date) RSS. Available at: https://islamqa.info/en/answers/82120/the-reason-why-the-right-hand-is-preferred-over-the-left (Accessed: 30 November 2023).

Tyr: The god of war and lord of one hand (no date) Valhalla hidromiel. Available at: https://valhallahidromiel.com/gb/blog/news/tyr-the-god-of-war-and-lord-of-one-hand (Accessed: 28 November 2023).

Section 2

Adusumilli, P.S. et al. (2004) ‘Left-handed surgeons: Are they left out?’, Current Surgery, 61(6), pp. 587–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2004.05.022.

Apa PsycNet (no date) American Psychological Association. Available at: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0033-295X.104.4.714 (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Anderson, M. et al. (2017) ‘Challenges training left-handed surgeons’, The American Journal of Surgery, 214(3), pp. 554–557. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.12.011.

Gallup, A.C. and Sleicher, E. (2021) ‘Left-hand advantage and the right-sided selection hypothesis.’, Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), pp. 184–190. doi:10.1037/ebs0000245.

Goodman, J. (no date) The wages of sinistrality: ‘handedness’, brain structure, and human capital accumulation, Journal of Economic Perspectives. Available at: https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257%2Fjep.28.4.193 (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Hagemann, N. (2009) ‘The advantage of being left-handed in Interactive Sports’, Attention, Perception & Psychophysics, 71(7), pp. 1641–1648. doi:10.3758/app.71.7.1641.

Jäncke, L., Schlaug, G. and Steinmetz, H. (1997) ‘Hand skill asymmetry in professional musicians’, Brain and Cognition, 34(3), pp. 424–432. doi:10.1006/brcg.1997.0922.

Judge, J. and Stirling, J. (2003) ‘Fine Motor Skill Performance in left- and right-handers: Evidence of an advantage for left-handers’, Laterality: Asymmetries of Body, Brain, and Cognition, 8(4), pp. 297–306. doi:10.1080/13576500412331325342.

Kaya, M.D. and Orbak, R. (2004) ‘Performance of left-handed dental students is improved when working from the left side of the patient’, International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 33(5), pp. 387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ergon.2003.09.006.

Keenan, J.P. et al. (1999) ‘Left hand advantage in a self-face recognition task’, Neuropsychologia, 37(12), pp. 1421–1425. doi:10.1016/s0028-3932(99)00025-1.

Kolgraf, J. (2023) 14 musicians you didn’t realize were left-handed, SiriusXM. Available at: https://blog.siriusxm.com/left-handed-musicians (Accessed: 14 January 2024).

Kopiez, R. et al. (2011) ‘No disadvantage for left-handed musicians: The relationship between ‘handedness’, perceived constraints and performance-related skills in string players and pianists’, Psychology of Music, 40(3), pp. 357–384. doi:10.1177/0305735610394708.

Minnesota Orchestra (2022) The left stuff: Left-’handedness’ in the music world, The Left Stuff: Left-’handedness’ in the Music World - Minnesota Orchestra. Available at: https://www.minnesotaorchestra.org/stories/the-left-stuff-left-’handedness’-in-the-music-world/ (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Mixdown (2023) The 13 most iconic left-handed guitarists of all time, Mixdown Magazine. Available at: https://mixdownmag.com.au/features/columns/the-13-most-iconic-left-handed-guitarists-of-all-time/ (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Oldfield (1969) ‘handedness’ in musicians. Available at: https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1969.tb01181.x (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Taras, J.D., Behrman, M. and Degnan (1995) Left-hand dominance and hand trauma, The Journal of hand surgery. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8583055/ (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Tchantchaleishvili, V. and Myers, P.O. (2010) ‘Left-’handedness’ — a handicap for training in surgery?’, Journal of Surgical Education, 67(4), pp. 233–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.06.001.

Walker, N. (2020) Can the violin be played left-handed?: Normans blog, Normans Musical Instruments. Available at: https://www.normans.co.uk/blogs/blog/can-the-violin-be-played-left-handed (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Why are left-handers called ‘southpaws? (no date) History.com. Available at: https://www.history.com/news/why-are-left-handers-called-southpaws (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Zürich, U. of (2002) The case of a left-handed pianist playing a reversed...: Neuroreport, LWW. Available at: https://journals.lww.com/neuroreport/citation/2002/09160/the_case_of_a_left_handed_pianist_playing_a.1.aspx (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

(2014) Why left-handers/footers are overrepresented in some sports? Available at: https://mjssm.me/clanci/MJSSM_Sept_2014_Akpinar_33-38.pdf (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Section 3 & Conclusion

Babu, R. (2019) Inclusivity Guide: Usability Design for left ‘handedness’ 101, Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/@rubenbabu/inclusivity-guide-usability-design-for-left-’handedness’-101-2bc0265ae21e (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Bock, L. (2014) You don’t know what you don’t know: How our unconscious minds undermine the workplace, Google. Available at: https://blog.google/inside-google/life-at-google/you-dont-know-what-you-dont-know-how/ (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Fisher, S. and Papadatou-Pastou, M. (2021) Left-handed workers in a right-handed world: The future of work podcast, ILO Voices. Available at: https://voices.ilo.org/podcast/left-handed-workers-in-a-right-handed-world (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Gender less voice - genderless voice (2019) Genderless Voice. Available at: https://www.genderlessvoice.com/ (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

How unconscious bias affects design (2023) The Art of Crafting User Stories. Available at: https://subscription.packtpub.com/book/business-and-other/9781837639496/2/ch02lvl1sec19/how-unconscious-bias-affects-design (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Humm, S. (2015) 20% of left-handed employees face problems in the workplace, HRreview. Available at: https://hrreview.co.uk/hr-news/strategy-news/20-left-handed-employees-face-problems-workplace/58739#:~:text=One in five employees experience,-Handers Day (Thursday). (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

IOS 14.5 offers unlock iphone with Apple Watch, diverse Siri Voices, and more (2023) Apple Newsroom. Available at: https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2021/04/ios-14-5-offers-unlock-iphone-with-apple-watch-diverse-siri-voices-and-more/ (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Kreatr, K. (2023) Right-handed bias: Unseen Privileges revealed, Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/@kreatr22/right-handed-bias-unseen-privileges-revealed-d9ee4851cdfd (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Kurtzleben, D. (2014) Study: Left-handed people earn 10 percent less than righties, Vox. Available at: https://www.vox.com/2014/12/5/7318823/pay-gap-left-handers (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

McCracken, H. (2012) Confessions of a left-handed technology user, Time. Available at: https://techland.time.com/2012/08/27/left-handed-technology/ (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Ocklenburg, S. (2023) Left-’handedness’: What is right-hand bias? - psychology Today, Psychology Today. Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/the-asymmetric-brain/202307/left-’handedness’-what-is-right-hand-bias (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Scope (2023) Accessible fonts for easier readability: The basics, Scope for business. Available at: https://business.scope.org.uk/article/font-accessibility-and-readability-the-basics (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Understanding accessibility requirements for public sector bodies (2023) GOV.UK. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/accessibility-requirements-for-public-sector-websites-and-apps#:~:text=The accessibility regulations came into,accessibility statement on your website. (Accessed: 06 January 2024).

Wichary, M. (1995) Guidebook > ... > slideshows > microsoft mouse 2.0. Available at: https://guidebookgallery.org/ads/slideshows/microsoftmouse20 (Accessed: 06 January 2024).